I have a new piece on the London Review of Books Blog about a vicious South Park-style cartoon that has been banned in China. WARNING: some animated rabbits get hurt.

Category Archives: china

In Defense of Lost Causes

After my conversation with the organisers of the July 2009 Urumqi protests, I’ve been thinking a lot about protest, in all its forms. Slavoj Zizek’s In Defense of Lost Causes is a book that aims to convince the reader that the ills of the world will not be solved peacefully. What is needed, he argues, is revolutionary terror. The book is a sustained attack on the idea that tolerance and democratic debate are going to effect meaningful change (which for Zizek means the end of capitalism). It’s a complicated book whose argument wanders at times, and occasionally gets lost in score-settling, or Hegelian nitpicking, but it is always readable, provocative and entertaining, not least because for Zizek everything- whether it be Shakespeare or a Jennifer Anniston film -can be illustrative. As a Pynchon scholar I was particularly interested in how he deals with alternative communities, whether or not these are genuinely subversive, or just a form of escape which does nothing to threaten that which they are fleeing from. If I rely heavily on Zizek’s quotes to summarise some of the book’s main arguments, it’s because it seems a safer way to avoid any ‘violence’ to his ideas.

The book’s aim “is not to defend Stalinist terror, and so on, as such, but to render problematic the all-too-easy liberal-democratic alternative… the misfortunes of the fate of revolutionary terror confront us with the need- not to reject terror in toto, but- to reinvent it” (6-7).

In terms of the accepted ideas about which to put a human face to capitalism, he argues that “When one confronts a world which presents itself as tolerant and pluralist, disseminated, with no center, one has to attack the underlying structuring principle which sustains this atonality- say, the secret qualifications of “tolerance” which excludes as “intolerant” certain critical questions, or the secret qualifications which exclude as a “threat to freedom” questions about the limits of the existing freedoms. (30)

He goes on to critique the idea of opting out of the system:

“Postmodernity” as the “end of grand narratives” is one of the names for this predicament in which the multitude of local fictions thrives against the background of scientific discourse as the only remaining universality deprived of sense. Which is why the politics advocated by many a leftist today, that of countering the devastating world-dissolving effect of capitalism modernization by inventing new fictions, imagining “new worlds”… is inadequate or, at least, profoundly ambiguous: it all depends on how these fictions relate to the underlying Real of capitalism- do they just supplement it with the imaginary multitude, as the postmodern local narratives do, or do they disturb its functioning? (33)

Zizek is withering about the way in which many of our ‘ethical’ choices involve choosing how we consume:

True freedom is not a freedom of choice made from a safe distance, like choosing between a strawberry cake and a chocolate cake; true freedom overlaps with necessity, one makes a truly free choice when one’s chouice puts at stake one’s very existence- one does it because one simply “cannot do otherwise.” When one’s country is under foreign occupation and one is called by a resistance leader to join the fight against the occupiers, the reason given is not “you are free to choose,” but: “Can’t you see this is the only thing you can do if you want to retain your dignity?” (70-71)

At times the worldview he presents veers towards a form of Gnosticism (much like Pynchon’s):

The fact that God created the world does not display His omnipotence and excess of goodness, but rather his debilitating limitations. (153)

Many of the book’s best lines belong to Robespierre. This is his riposte to the moderates who deplored the excesses.

Citizens, did you want a revolution without a revolution? What is this spirit of persecution that has come to revise, so to speak, the one that broke our chains? But what sure judgement can one make of the effects that follow these great commotions? Who can mark, after the event, the exact point at which the waves of popular insurrection should break? (163)

Robespierre addressing those who complained about the innocent victims of revolutionary terror: “Stop shaking the tyrant’s bloody robe in my face, or I will believe that you wish to put Rome in chains”. (471)

On the anti-globalisation movement:

This movement also succumbs to the temptation to transform a critique of capitalism itself (centred on economic mechanisms, forms of work organization, and profit extraction) into a critique of “imperialism”… with the (tacit) idea of mobilizing capitalist mechanisms within another, more “progressive” framework. (181)

On the power of ‘failed’ revolutionary Events:

The ultimate factual result of the [Chinese] Cultural Revolution, its catastrophic failure and reversal into the recent capitalistic transformation, does not exhaust the real of the Cultural Revolution: the eternal Idea of the Cultural Revolution survives its defeat in socio-historical reality, it continues to lead an underground spectral life of the ghosts of the failed utopias which haunt the future generations, patiently awaiting their next resurrection. (207)

With reference to Pynchon and the failed Utopias that appear in his work (such as Lemuria in Inherent Vice), it makes me think that though it can be a form of escape, to posit some form of Utopia is always an essentially hopeful act.

For Zizek, the real problem is what happens after a revolutionary Event, how one keeps revolutionary momentum.

The problem is thus: how to regulate/institutionalize the very violent egalitarian democratic impulse, how to prevent it being drowned in democracy in the second sense of the term (regulated procedure)? If there is no way to do it, then “authentic democracy” remains a momentary utopian outburst which, on the proverbial morning after, has to be normalized. The harsh consequence to be accepted here is that this excess of egalitarian democracy over the democratic procedure can only “instituinalize” itself in the guise of its opposite, as revolutinary democratic terror. (266)

One of Zizek’s main strengths is overturning conventional wisdom about what rhetorical positions we should occupy:

The influx of immigrant workers from the post-Communist countries is not the consequence of multiculturalist tolerance- it is indeed part of the strategy of capital to hold in check workers’ demands… the lesson the Left should learn from it is that one should not… merely oppose populist anti-immigration racism with multiculturalist openness, obliterating its displaced class content (267)

Given how much of Pynchon’s work deals with delusion and escape, I was interested in what Zizek has to say about fetishes:

They can be our inner spiritual experiences (which tell us that our social reality is mere appearance which does not really matter), our children (for whose good we do all the humiliating things in our jobs) and so on and so forth (298)

Fetishists are not dreamers lost in their private worlds, they are thoroughly “realist”, able to accept the ways things effectively are- since they have their fetish to which they can cling in order to canel the fall impact of reality. (296)

Zizek on how democracy has its own constraints:

When Rosa Luxembourg wrote that “dictatorship consists in the way in which democracy is used and not in its abolition” her point was not that democracy is an empty framework which can be used by different political agents (Hitler also came to power through- more or less -free democratic elections), but that there is a “class bias” inscribed into this. (379)

Zizek then goes on to offer what looks like an argument in favour of some kind of revolutionary faith, without which one cannot see the potential for change.

Liberals claim that capitalism is today so global and all encompassing they they cannot “see” any serious alternative to it… The repy to this is that, in so far as this is true, they do not see tout court: the task is not to see the outside, but to see in the first place (to grasp the nature of contemporary capitalism)- the Marxist wager is that, when we “see” this, we see enough, including how to go beyond it. (393)

The following seems to be a fairly clear endorsement of ‘violence’ (though what that means is not yet clear, i.e. is it literal violence or symbolic?)

One should not renounce violence ; one should rather reconceptualise it as defensive violence, a defense of the autonomous space created by subtraction (408)

Zizek also offers a way of evaluating subtraction (e.g. the alternative communities that occur throughout Pynchon, especially in Vineland).

Is it a subtraction/withdrawl which leaves the field from which it withdraws intact (or even functions as its inherent supplement , like the “subtraction” from social reality to one’s true Self proposed by New Age meditation); or does it violently shake up the field from which it withdraws? (412)

It’s only in the afterword that Zizek starts to signal what he might mean by ‘violence’. Unfortunately, this seems to shift, initially from a kind of eye-of-the-beholder definition of violence (that differentiates between “radical emancipatory violence against the ex-oppressors and the violence which serves the continuation and/or establishment of hierarchical relations of exploitation and domination” (471)) to talk of violence that is really non-violence. He calls for

a passive revolution which, rather than directly confronting power , gradually undermines it in the manner of the subterranean digging of a mole, through abstaining from particiapation in the everyday rituals and practices that sustain it. (474)

However, Zizek concludes by arguing that the distinction between literal violence and non-violence is less important than whether the “violence” is “divine violence”.

What is and what is not divine violence?… it can appear in many forms: from “non-violent” protests (strikes, civil disobedience) through individual killings to organized or spontaneous violent rebellions and war proper. (483)

As for evaluating such acts, these are said to be

located ‘beyond good and evil’, in a kind of politico-religious suspension of the ethical. Although we are dealing with what, to an ordinary moral consciousness, cannot but appear as “immoral” acts of killing, one has no right to condemn them, since they are the reply to years, centuries even, of systematic state violence and economic exploitation. (478)… If a class is systematically deprived of their rights, of their very dignity as persons, they are eo ipso also released from their duties toward the social order, since this order is no longer their ethical substance. (479)

This is about as unambiguous as it gets:

Sometimes one has to kill in order to keep one’s hands clean; not as a heroic compromise of dirtying one’s hands for a higher goal. (484)

However, in the final pages, Zizek again muddies the waters by suggesting that no one is able to pass judgement on whether an act of violence is ‘divine’ or not, which if he means it, to some extent undermines many of the judgements he passes on the value of various failed revolutions.

There are no “objective” criteria enabling us to identify an act of violence as divine: the same act, that to an external observer, appears merely as an irrational outburst of violence, can be divine for those engaged in it. (485)

The subtleties of this may be lost on me. But to me this seems dangerously close to denying us the right to condemn the killings by a lynch mob, the suicide bomber in a school, or acts of ethnic cleansing.

The Year of the Metal Tiger: A review.

I review some of the main events this year in China at n+1, along with contributions from Yelena Akhtiorskaya, Siddhartha Deb, Eli S. Evans, Keith Gessen, Chris Glazek, Emily Gould, Elizabeth Gumport, Alice Gregory, Charles Petersen, Nikil Saval, Jonathan Watson, and Emily Wit.

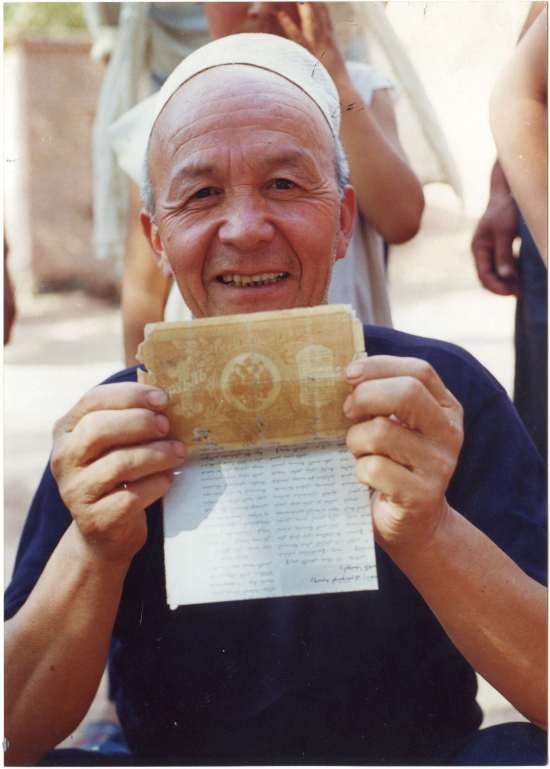

Street Scene, Urumqi, 1957

Richard Hughes was a journalist who spent most of his life as a correspondent in Asia for The Times, The Economist, and the Far Eastern Economic Review. During World War 2 he was thought by some to be a spy, and possibly a double agent. Given these suspicions, it is unsurprising that he ended up being fictionalised twice: Ian Fleming based the character of Dikko Henderson in You Only Live Twice on him; in John Le Carre’s The Honourable Schoolboy he appears as Craw. This is his from book Foreign Devil, a memoir. I quote this because a) it suggests how relations (not to say manners) have worsened in the city known as ‘beautiful pastureland’ and b) I have a weakness for this kind of prose.

It happened in ‘The Street of the Grey-Eyed Men’ during the tranquil noontime traffic ‘rush’. The inexpert Chinese driver of a bus loudly tooted his horn and frightened a nervous, highstepping white mare, ridden by a tough Kazakh tribesman. The horse reared, neighing, and fell. The horseman skillfully sprang clear, raised and soothed the mare, handed the reins with a bow to the chairman of a council of dignified nomads seated in converse in the gutter, walked calmly over to the halted bus, and, with deliberation but no visible anger, fetched the apologetic driver a fearful backhand clout over the nose. He then remounted, saluted his quietly approving audience in the gutter, and rode off. The Chinese driver wiped his nose, bowed first to the seated gallery, arose, turned and bowed next to the amused but friendly passengers, and drove off, without tooting.

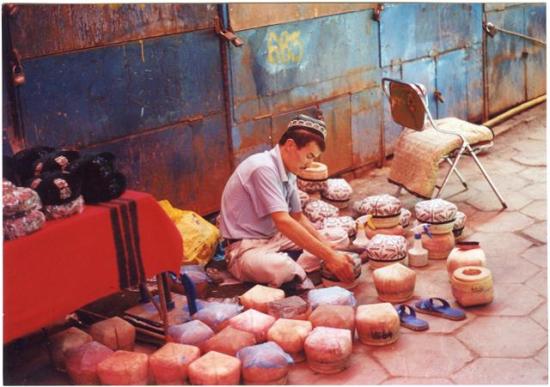

New photos from Yining

Some photos of the market and back streets in Yining, where I used to live. These were taken in April 2010- there are more up on my Flickr site.

‘Whether you have a boy or girl, it is still a blossom’

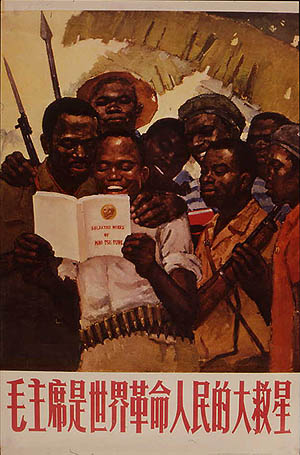

More Chinese Propaganda Posters, this time from the large collection at the University of Westiminster (thanks to Jeff Wasserstrom for making me aware of the collection).

The collection spans the period between the late 1960s and the late 1980s. John Gittings, then Senior Lecturer of the Chinese Section, began the collection in 1979 as the China Visual Arts Project for research and teaching purposes. Over the years it grew, with the contributions of other colleagues, students and friends who studied and travelled in China.There are over 500 images in the collection, which is organised thematically.

‘Love the motherland’

I have some pictures of Chinese propaganda murals on the LRB Blog

Twentieth-Century Xinjiang

I recently came across this excellent Blog on Xinjiang’s history, which has made me painfully aware of how much of a non-expert I am on this subject (not to mention…). There’s a great deal of thoughtful analysis on a wide variety of topics, from the deaths of the leaders of the East Turkestan Republic, to UFO sightings in the region. I’d particularly recommend the posts on the Photos of J. Hall Paxton, who was U.S. Consul-General in Urumqi from 1946 through 1949. The captions on the photos below particularly caught my eye.

More ordinary things

Some small restaurants in Shaoyang, the town in Hunan where I first taught. Probably my favourite places to eat in the world.

Flickr set of Urumqi

Some photos I took in Urumqi this spring are up at Flickr now.

‘A Bright Pearl of the Western Region’

I have a new piece on the London Review of Books Blog about the plans to stimulate Xinjiang’s economy, and my doubts that the gains will be shared equally.

Ethnic unity, Language and Discos.

A few good recent Xinjiang pieces, the first from Kashgar about the different responses to the massive social and cultural changes in the city caused by the destruction of the old town. The video is well-worth watching, and gives a sense of the scale of the demolition.

In the wake of the Tibetan language protests in Qinghai and elsewhere, minority education as a whole is getting more attention. The Uighur Human Rights Project has a very good piece on the issues of so-called ‘bilingual education’, and the obvious political dimensions. The article focuses on a report that appeared in the Chinese press about a visit to a school in Tongxin, in the Kizilsu Kirghiz autonomous area of Xinjiang. The article notes that Tongxin Middle School’s facilities are almost the same as those of schools in eastern China, except for that

“in every classroom, next to the teacher’s podium there is a poster proclaiming an “ethnic unity” pledge, with the second line stating that “every teacher and student should, in thinking and behavior, be fully conscious that the biggest danger to Xinjiang derives from “ethnic splittism” and “illegal religious activities”.

Finally, there’s a review of an interesting new book on the region by Gardner Bovingdon. My grasp of Uighur was, at best, pretty tenuous, so I always had to rely on what people could tell me in English. As a result, I’m particularly interested in the part of the book that deals with

the number of daily public and private ways the Uyghur people defy the Chinese regime. From jokes to songs to stories, Uyghurs invoke the symbols of opposition to Chinese authorities. These varieties of resistance either circulate in trusted private conversations or in allegorical form at public performances.

Not a story about violent ethnic conflict

Having just posted that fairly bleak piece about the likelihood of further violence in Xinjiang, here’s a slightly more optimistic one from Radio Free Asia. It doesn’t seem to have been picked up by other news outlets, for reasons that emphasise what constitutes ‘news’.

On October 15th around 100 farmers began protesting in Kashgar against the high fees they have to pay the government to use land. They stayed outside the prefectural government building in Kashgar for 3 days, when the protest came to an end, but not in the manner in which such protests usually do in Xinjiang.

“We had expected armed to police to come take us away, but actually, top officials including the county secretary and village party chief came. Most importantly, they treated us very nicely,” Yusupjan [the leader of the protest] said.

Officials pointed out to the protesters that they would have faced harsher treatment a year ago, after ethnic unrest broke between Uyghurs and Han Chinese in Urumqi, the regional capital. Uyghur men faced widespread arrests in the ensuing crackdown.

“The official said, ‘As you know, if this were last year, you could have seen yourselves surrounded by armed police and your destiny would have been the detention center. But that time is over and such a thing will not happen again. Please listen to us, follow us to return home and we can discuss anything you want with you.’”

The officials are said to have done so, and to be considering the request. Whether or not the land fees get adjusted, this is a unusual story because there seems to be a) agreement from both sides about what happened and b) the protest ended peacefully. I also find it remarkable how candid the officers were about what would usually happen- let’s hope this is due to some general edict about the need for more sensitive policing in the region.

‘A Perfect Bomb’

Here is, astonishingly, some actual reportage I did. It’s a long interview I did in Urumqi when I was there in April/May. It’s about protest, violence and terrorism, and will also appear, in some form, in The Tree that Bleeds.

26 seconds of backstreet action.

A snippet of film of a Uighur backstreet in Urumqi. Highlights include: faces, sounds, a table of bread, sparks from metal being struck.

Tibetan-language protest in Qinghai

There have been reports (1, 2) of a protest in the western province of Qinghai, where over 1,000 students yesterday marched about plans to restrict the use of the Tibetan language in schools. The protest was peaceful, and the police made no attempt to stop the demonstration. Free Tibet said the protests were caused by educational reforms already implemented in other parts of the Tibetan plateau, which order all subjects to be taught in Chinese and all textbooks to be written in Chinese, except for Tibetan language and English classes.

I don’t have much to add, other than to say that the same thing is happening in Xinjiang, where the Uighur language will soon no longer be used in schools and universities. This is not a new phenomena- in 2001, when I taught in Xinjiang, there were already Uighur children who had gone to predominantly Han schools (‘Min Kao Han’ students) who couldn’t read or write Uighur (which is written using a modified Arabic script:

ھەممە ئادەم زاتىدىنلا ئەركىن، ئىززەت-ھۆرمەت ۋە ھوقۇقتا باب-باراۋەر بولۇپ تۇغۇلغان. ئۇلار ئەقىلگە ۋە ۋىجدانغا ئىگە ھەمدە بىر-بىرىگە قېرىنداشلىق مۇناسىۋىتىگە خاس روھ بىلەن مۇئامىلە قىلىشى كېرەك.

(‘All human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights. They are endowed with reason and conscience and should act towards one another in a spirit of brotherhood’)

Of course, this only matters if you think that language has anything to do with culture or identity. While it is a good thing for everyone to have a language they can communicate in (Chinese, English), this shouldn’t be at the expense of the language that their culture relies on.

Fortune-telling in Urumqi

A few words

There’s a brief Q. and A. on the Luath website about my forthcoming book, The Tree That Bleeds.

‘God is doing great things in China’

On August 24 the BBC reported that the Chinese government is encouraging the development of Christianity within the country. In addition to supporting the establishment of national seminaries for Catholic and Protestant clergy, the government has provided land, and 20% of the building costs, for a new church in Nanjing, which when completed will be the largest in the country. An official told the BBC that there are at least 20 million Protestants legally worshipping in churches in China. Though this may come as a surprise (on the grounds that a Communist state might be expected to oppose religion), freedom of belief is provided for by article 36 of the Chinese constitution.

It justifies this by arguing that ‘People in China, whether they are religious believers or not, in general love their motherland and stand for socialism. They all work for the country’s socialist modernisation programme. So, it is easy to see that the policy ensuring freedom of religious belief for all citizens is in no way against socialism.’

But although religion is tolerated, there are many restrictions on how people can worship. Believers must worship in registered venues, and all religious publications and appointments must be approved by the authorities. It is this level of surveillance that leads people to worship in house churches throughout the country, which not being registered, are considered illegal. For many years, human rights organisations have criticised the treatment of people arrested for attending these churches, many of whom, according to Amnesty International, ‘continue to experience harassment, arbitrary detention, imprisonment and other serious restrictions’.

Though the government claims that its goal in encouraging Christianity is to ‘better guarantee religious belief in China’, the official the BBC spoke to also made it clear that ‘the Chinese Communist Party believe there is no God in the world’. However, there are other reasons why the government may wish to encourage Christianity. One is that the government could be trying to bring more worshippers into open, where it can keep a watchful eye on them. Another, more pragmatic explanation, is to do with the social role a strong Church might fulfill. In the past, the Communist Party has sought to prevent the formation of national organisations outside the state’s control (such as its campaign against the Falun Gong), fearing these might serve as a focal point for dissent. But as the gap between the rich and poor increases in China, non-state organisations may be needed to deal with the social problems (drug use, homelessness, poverty) likely to result. Given that, in a recent survey of charitable behaviour, China came 147th out of 153 countries surveyed on measures like volunteering and giving to charity, the government may be hoping that state-run churches will encourage a growth in social consciousness. Whatever the reason for the government’s shift in policy, it has been welcomed by many Chinese Christians. One student interviewed by the BBC said, ‘I think this nation will change, and I think God is doing great things in China.’

Burning Books

I have a piece in the latest London Review of Books. This is how it begins:

I began burning books during my third year in China. The first book I burned was called A Swedish Gospel Singer. On the cover there was a drawing of a blonde girl wearing a crucifix with her mouth wide open and musical notes floating out of it. Inside was a story, written in simple English, about a Swedish girl who loved to sing. One day, passing a church, she heard a wonderful sound. When she went in, the congregation welcomed her and asked her to join their gospel choir. Through these songs she learned about Jesus, his compassion, his sacrifice, the love he feels for all.

It was originally longer, and took in all kinds of other personal stuff, but I think they kept the core. There’s no better cure for one’s tendency to be precious than having a thousand words just cut.

Suspicious Timing

I have a brief piece on the London Review of Books blog about the recent arrest of a ‘terror cell’ in Xinjiang, conveniently just in time for the one year anniversary of the Urumqi riots.

Minor update

Looks like my book, The Tree That Bleeds: A Uighur Town on the Edge, will be out in early October, at least according to Amazon. No doubt the thinking is that it will clean up at Xmas, which is of course the time of year when people are desperate to buy books about riots and ethnic tension. On Xmas day, I may recreate that scene from The Doors where Jim Morrison gives the rest of the band presents, which pleases them greatly, till they open them and find that they have each been given a copy of his book of poems. [following sentence deleted out of an attempt to preserve reasonable family relations].

Problems for Adam and Eve

From Jo McMillan’s piece on Chinese sex shops in the current issue of Granta:

Dr Wang opens her eyes. She is ready now to pronounce, to prescribe for my lack of man. She fishes keys from her pocket and unlocks a cabinet. ‘This is what you need,’ she says, and offers me a pink baton, a face moulded into the head, the shaft embossed with rows of nodules that look – here, in this clinic, in this doctor’s hands – like an unusually disciplined rash. She balances the vibrator in the tips of her fingers, showing it off to me. I catch the smell of garage forecourts.

Having stayed in a lot of Chinese hotels over the last few months, I am pleased to report that the quality and range of sexual health products supplied in the rooms has improved immeasurably from 8 years ago. Though there are still the lotions that misleadingly promise genital hygiene (which are dangerous, in that their use dissuades people from using more reliable methods of prevention) there are now always condoms as well, sometimes for free (for instance in Yining, which has a high rate of HIV infection).

N+1

I have an update on the situation in Xinjiang at N+1.

Here are some more photos I took while cowering behind cars:

Fair trade, Apple?

Good piece in The Guardian about the routine breach of health conditions by those who make our shiny toys (sorry meant to say ‘iPhone manufacturers’).

Stranded

I have a little post on the LRB Blog today, about being stuck in Beijing.

798, Beijing

Despite my best efforts to do nothing in Beijing other than sit in a room and type while I wait for the flight that KLM so graciously gave me on May 4th, two weeks after my original flight was cancelled, I still occassionally find myself somewhere that threatens to undermine my dislike of this city. 798 is a district given over to galleries and studios, in the north east corner of the city not far from the airport. It began in the mid-90s, when artists were looking for cheap spaces and found that the closed factories of the district were available.

As in every other place in the world, most of the art was terrible: dull, derivative, overly conceptual. But there were things I liked (pictured below), most of all the sense of being in a Cultural space, which at the risk of making a horribly insulting, not to say idiotic generalisation, is not all that common in China, even in the highly developed cities of the east coast.

Sunday in Shanghai

Before this I was in Beijing. Perhaps, without crippling jet lag, it might have been fine. But with this, and the dust storm, it was pretty dreadful.

Shockingly, I only have good things to say about Shanghai. It is clean and modern without being antiseptic. Behind East Nanjing Road (pictured below) there are still smaller, older streets without the hysteria of consumerism. As posters on every surface tell us: only 4o days till EXPO! This is a huge international gathering of ideas about architecture and design- the stills look very promising.

Next stop: Huizhou, about which I know nothing other than that my old colleauge Mr Ma (who used to be a spy) is now teaching there.

SCA talk

I’ll be giving a talk about Xinjiang to the Scotland China Association on Tuesday 9th March in Edinburgh. It will be in the library of The Friends Meeting House on Victoria Terrace (at the foot of the lane down from the Lawnmarket, at the top of the stairs down to Victoria Street). From 7-9 p.m.

Scottish Arts Council Grant

I’m pleased to say I’ve been awarded a professional development grant by the Scottish Arts Council which will help fund a trip to China in March. The purpose of the trip is to visit my old students, most of whom are either in the south east, around Guangzhou (which can be considered the new workshop of the world), in the south, in Hunan province (far poorer, more agricultural) or in the far west, in Xinjiang. I’m primarily interested in how they’ve fared in the far more open (and far more perilous) labour market that developed in the last decade. While all trained to be teachers, many have found their way into other occupations (soldier, businessman, postal worker), often in regions far from their hometowns. It is also possible that I may visit some interesting places in Xinjiang and have interesting conversations, and that these conversations, should they occur, may or may not help me understand the events of last summer and autumn.

It looks like The Tree that Bleeds will be out in the summer.