My post on Blockupy Frankfurt is now up on the London review of books blog. Thomas Seibert was a fascinating, engaging interviewee, and I’m very grateful to him for talking to me.

Category Archives: Articles

The City of the Dead

My piece on life in Cairo’s cemeteries is up at Egypt Independent.

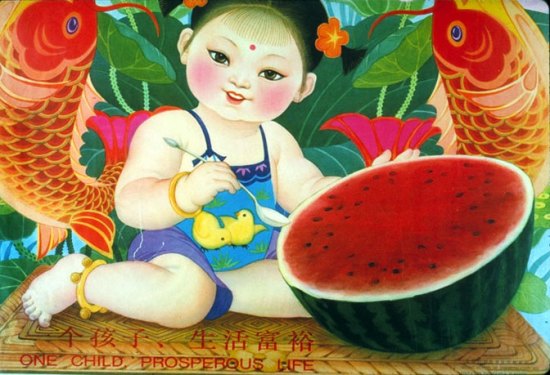

‘Boys and Girls Are All Treasures’

These, and other friendly slogans are considered in my piece for The Times of India on China’s new approach to the one-child policy.

Apparently, I used to be a scientist

My CV says that I have a Bsc in Experimental Psychology, and an Msc in Neuroscience. I seem to remember going for an interview at Oxford University for a PhD. The latter, I am sure, did not go any further, and probably mercifully. By the end of my masters I was very disenchanted with the practice of scientific research, in particular the way in which research seemed to follow scientific fashion, which is to say, funding. It was also disappointing to find many scientists, both at the start of their careers, and further on, who seemed to have little interest in theoretical questions.

Perhaps this was my own fault for having unrealistic expectations. Scientific research is not cheap, and needs to be focussed on details. But by the time I went to China in 1999, I had stopped taking even a passing interest in science. I didn’t read popular science books. I ignored headlines.

Last week, while logging into my email account, I saw a headline that made me stop, click, then read. Channel 4 had reported that a blood test for variant Creuztfeldt Jakob Disease was now available for use in UK hospitals.

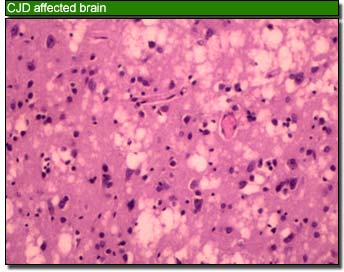

Few people today seem worried about mad cow disease (the popular name for variant Creutztfeldt Jakob Disease). In the late 1990s people spoke of vCJD like it was the new Black Death. All the newspapers, both broadsheet and tabloid, contained harrowing stories of otherwise healthy people developing symptoms that looked like a mixture of Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s Disease. Memory loss, personality changes, and hallucinations were accompanied by impaired speech, seizures, and problems with movement. Most patients died within 6 months, often of respiratory complications. The fact that vCJD’s symptoms overlapped with so many other neurological conditions meant there was no reliable diagnostic method until a post-mortem examination of the brain could be carried out. Only then it was possible to see the tiny holes in the brain tissue caused by massive cell death (which give it a sponge-like appearance) and to test for the presence of abnormal proteins.

One of the most frightening aspects of the disease was that there was no way to be certain you did not have it. CJD appears in a number of forms: an inherited form; one that occurs spontaneously due to a genetic defect; and one transmitted through the use of contaminated surgical instruments. In the case of vCJD, the cause was thought to be ingestion of beef products infected with Bovine Spongiform Encephalopathy (hence ‘mad cow disease’). It wasn’t just people who ate meat that had reason to be worried; any food containing meat by products (such as gelatin) was a potential risk. It was a wonderful time to be vegan.

In 1997, when I was still a scientist, I did a research project at the CJD Suveillance Unit in Edinburgh- I wrote about this, and what the availability of blood tests means on the LRB Blog yesterday. It made me briefly feel like someone who actually knows something about science. No doubt, this will pass.

Here is a photo of my supervisor Professor James Ironside, looking incredibly tough.

Frontex and human rights abuses in Greece

I wrote a post on the CITSEE website about human rights abuses being sanctioned by Frontex, the European Union border agency. It’s about the terrible conditions for non-EU migrants arrested trying to get into Greece and Bulgaria, and how an EU organisation seems to care more about ‘security’ than basic human rights.

The Yugosphere

My piece on the idea of a Yugosphere, and the problems of referring to the region that was Yugoslavia, is now up at Citizenship in South Eastern Europe (CITSEE), which is part of the Faculty of Law at the University of Edinburgh. There’s also lots of other good material on the region, including photo reportage and interviews.

Occupy, Prague

I have a post on the LRB Blog about the Occupy Protest in Prague last Saturday. Here’s some video of it as well.

The Book of Crows- A Review

My review of Sam Meekings’ The Book of Crows- a novel set in different time periods in China -is in the new issue of Edinburgh Review.

The Book of Crows by Sam Meekings (Polygon)

How did people think and speak a thousand years ago? The simple answer is: we don’t know. Without recorded speech, or transcripts, the best a historian can do is guess. So when we read a historical work of fiction what matters is not so much the accuracy of the characters’ thoughts and language, but whether they seem plausible. Sam Meeking’s second novel, The Book of Crows, attempts to ventriloquise characters from four different periods in Chinese history: a young girl in the 1st Century BCE who is kidnapped and taken to a brothel; a grieving poet in the 9th Century; a Franciscan monk in the 13th Century; and a low ranking civil servant in the early 1990s. What these disparate narrators have in common is that they encounter people determined to find a mythical book that contains the entire past, present and future history of the world.

Meekings is to be commended for his ambition in trying to weave these separate narratives together, not so much at the level of plot, but in terms of parallels between the different narrators. The poet, the kidnapped girl, and the civil servant all share a degree of fatalism, which accords with the ideas of predestination and fate raised when different characters debate whether the knowledge offered by the mythical book is more a curse than a blessing. ‘Rain at Night’, the story of the grieving poet, is by far the most affecting of the different strands. Though Bai Juyi‘s grief for his daughter is dealt with in a mostly oblique fashion, there is a delicacy and sadness to his narration. His discussion of poetry with the crown prince is an impressively nuanced scene that functions as both a literary and spiritual lesson. Though some of his expositions of Buddhist precepts feel a trifle forced (‘…for a while we shared our common experiences of finding solace in the words of the Buddha, in the first realisation of the illusory nature of the world and, therefore, of the self.’), for the most part the voice remains compelling, especially with each section’s epigrammatic closing statement (e.g. ‘I say a sutra that your shoes stay strong, that your palms stay open’).

Unfortunately, this lightness of touch is absent in the novel’s other strands. Though Meekings does well in conjuring the different places and time periods, in the main his characters fail to convince on either a psychological or linguistic level. ‘The Whorehouse of a Thousand Sighs’ is narrated in a faux-British manner that makes it very hard to believe that events are taking place in 1st Century BCE China. People speak of ‘winding us up’, being ‘pretty pissed off’, or say they ‘needed to pee’. When a cook says, ‘And knock me over if it doesn’t look longer than the bloody desert itself’, it verges on Cockney. There is also a general portentousness to these sections, not only in the dialogue (‘She didn’t just buy our bodies: she bought our lives, our hopes, our dreams, our futures’) but also in the sententious tone of the young narrator, who has a frequent (not to say unconvincing) tendency to deliver homilies such as ‘If you don’t speak of things, sometimes they get lost so deep that when you really need them the words are buried beyond your reach’ and, ‘Why can’t we keep our dreams to the present, to what we already have, instead of grasping at the future, the sky, the impossible?’

Another troubling feature about this strand is the almost romanticised treatment of a very young girl being abducted and forced to have sex with strangers. The girl rarely seems frightened, and when it comes to her first time, this is dealt with in a single, cursory paragraph.

The other two narrative strands are similarly plagued. The 13th Century monk’s expressions of prejudice and faith are so predictable that it is hard to retain interest. As for the civil servant in the 1990s (who also employs words like ‘wonky’ and ‘git’), some of his exclamations and statements are utterly implausible. ‘Thank the mighty Politburo!’ is a phrase that belongs only in propaganda. Meekings- who has lived in China –should also know better than to have his narrator say, ‘Some folks these days are nostalgic for the old Cultural Revolution’. This was certainly not the case in the early 1990s- it was far too fraught and recent a memory.

If The Book of Crows doesn’t succeed as either a collection of short pieces, or a novel (even one with a discontinuous narrative), this is partly because the attempt to recreate the thoughts and feelings of people from another time (not to mention another culture and language) must always carry a taint of the contemporary. In order for such characters and their worlds to be convincing, they need to be both linguistically and psychologically unfamiliar, so as to remove the reader from their language, time and culture. Otherwise the historical setting is what Lukacs called ‘mere costumery’. Though The Book of Crows offers us ‘curiosities and oddities’ from ancient China, its characters are too much of the present.

Arrests after the 2009 Urumqi riots

I have a new post on the LRB Blog about some footage of the arrests that followed the riots in Urümqi in 2009. The clip shows the fairly brutal treatment of suspects, not just by the police, but by the onlookers as well. It corroborates reports from eyewitnesses who spoke to Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch.

‘Civil Marriage, Not Civil War’

I have a new post on the London Review of Books Blog about the Secular movement in Lebanon. Here are some photos from the march on May 15th in Beirut.

Beirut graffiti

I have a new post on the London Review of Books Blog about the sectarian graffiti in Beirut. As per usual, it features an act of stupidity on my part.

“There is great chaos under heaven – the situation is excellent.”

Here’s Zizek’s take on the protests in Egypt:

Why fear the Arab revolutionary spirit? | Slavoj Žižek | Comment is free | guardian.co.uk

And here’s my summary of In Defense of Lost Causes

Rabbits vs. Tigers

I have a new piece on the London Review of Books Blog about a vicious South Park-style cartoon that has been banned in China. WARNING: some animated rabbits get hurt.

The Year of the Metal Tiger: A review.

I review some of the main events this year in China at n+1, along with contributions from Yelena Akhtiorskaya, Siddhartha Deb, Eli S. Evans, Keith Gessen, Chris Glazek, Emily Gould, Elizabeth Gumport, Alice Gregory, Charles Petersen, Nikil Saval, Jonathan Watson, and Emily Wit.

‘Love the motherland’

I have some pictures of Chinese propaganda murals on the LRB Blog

Zadie Smith on The Social Network

From Zadie Smith’s excellent piece on The Social Network in the latest NYRB.

World makers, social network makers, ask one question first: How can I do it? Zuckerberg solved that one in about three weeks. The other question, the ethical question, he came to later: Why? Why Facebook? Why this format? Why do it like that? Why not do it another way? The striking thing about the real Zuckerberg, in video and in print, is the relative banality of his ideas concerning the “Why” of Facebook. He uses the word “connect” as believers use the word “Jesus,” as if it were sacred in and of itself: “So the idea is really that, um, the site helps everyone connect with people and share information with the people they want to stay connected with….” Connection is the goal. The quality of that connection, the quality of the information that passes through it, the quality of the relationship that connection permits—none of this is important. That a lot of social networking software explicitly encourages people to make weak, superficial connections with each other (as Malcolm Gladwell has recently argued1), and that this might not be an entirely positive thing, seem to never have occurred to him.

I couldn’t agree more with the following.

Shouldn’t we struggle against Facebook? Everything in it is reduced to the size of its founder. Blue, because it turns out Zuckerberg is red-green color-blind. “Blue is the richest color for me—I can see all of blue.” Poking, because that’s what shy boys do to girls they are scared to talk to. Preoccupied with personal trivia, because Mark Zuckerberg thinks the exchange of personal trivia is what “friendship” is. A Mark Zuckerberg Production indeed! We were going to live online. It was going to be extraordinary. Yet what kind of living is this? Step back from your Facebook Wall for a moment: Doesn’t it, suddenly, look a little ridiculous? Your life in this format?

Yes, we should struggle against it. Yes, our lives are ridiculous. Not what happens, not what we think and feel, but certainly how we try to present ourselves to others. I don’t think there’s anyone I’ve gotten to know any better by being their ‘friend’ on Facebook. I know more about them, that’s all. But knowing which bands or films (or more rarely, books) other people like doesn’t bring us any closer. It does not make for a ‘connection’. It is just a way for us to spy on each other without the risk, or trouble, of actual interaction.

But I will not be quitting Facebook anytime soon. I do things that I want to tell people about, and I use Facebook for that, and it seems only fair that my Facebook ‘friends’ should get to tell me what they’re doing in return. It’s an exchange, a social transaction. But really nothing more.

Coetzee on Roth

From J.M. Coetzee’s review of Philip Roth’s latest novel, Nemesis.

How is it possible that we can knowingly act against our own interests? Are we indeed, as we like to think of ourselves, rational agents; or are the decisions we arrive at dictated by more primitive forces, on whose behalf reason merely provides rationalizations?

‘What the hell is water?’

This is the text of David Foster Wallace’s commencement address at Kenyon College in 2005. If anyone can find the full audio, there may be some sort of, um, ‘prize’.

Elif Batuman on Creative Writing Programmes

Elif Batuman on Creative Writing Programmes- The Posessed, her wonderful book on Russian literature, and those who love it, is out in the UK next year.

‘A conjuror of high magic to low puns’

It’s definitely more fun to write about being an academic than to actually do academic stuff.

As proof, I cite this piece of mine in n + 1 and Elif Batuman’s The Possessed.

***Thanks to The New Yorker, American Fiction Notes, The Millions, Longform.org, The New York Observer and other places for linking to the piece.

Blackwells and the Tories

I have a post on the LRB Blog about how Blackwell’s give a discount to Conservative Party members.

Burning Books

I have a piece in the latest London Review of Books. This is how it begins:

I began burning books during my third year in China. The first book I burned was called A Swedish Gospel Singer. On the cover there was a drawing of a blonde girl wearing a crucifix with her mouth wide open and musical notes floating out of it. Inside was a story, written in simple English, about a Swedish girl who loved to sing. One day, passing a church, she heard a wonderful sound. When she went in, the congregation welcomed her and asked her to join their gospel choir. Through these songs she learned about Jesus, his compassion, his sacrifice, the love he feels for all.

It was originally longer, and took in all kinds of other personal stuff, but I think they kept the core. There’s no better cure for one’s tendency to be precious than having a thousand words just cut.

Suspicious Timing

I have a brief piece on the London Review of Books blog about the recent arrest of a ‘terror cell’ in Xinjiang, conveniently just in time for the one year anniversary of the Urumqi riots.

N+1

I have an update on the situation in Xinjiang at N+1.

Here are some more photos I took while cowering behind cars:

A wooden tongue

From Ian Buruma’s review of the new William Vollman book in the latest NYRB:

If even our deepest desires are no more than delusions, then the objects of our desires are forever beyond our reach. But Vollmann, like most of us, though moved by the performance of Noh, is not ready for Buddhist renunciation. This, he writes, “is not what I wish to believe. I want to kiss the mask, and when I put my lips against its wooden emptiness, I want to feel a woman’s tongue in my mouth.”

Stranded

I have a little post on the LRB Blog today, about being stuck in Beijing.

This and that

A few things worth a look-

William Vollmann’s review of Ted Conover’s ‘The Routes of Man’; a new take on Salinger’s ‘A Perfect Day for Bananafish‘; the Great Male Novelists compared; why it isn’t worth being on Amazon sometimes; clip from the new Walker Percy documentary; and Zadie Smith’s rules for writers.

Coming to a shelf near you…

I have a piece on the London Review of Books blog about the use of video trailers for literary fiction. It features a wonderful animation for Kazuo Ishiguro’s Nocturnes, and also one of Pynchon giving a monologue.