Frontex and human rights abuses in Greece

I wrote a post on the CITSEE website about human rights abuses being sanctioned by Frontex, the European Union border agency. It’s about the terrible conditions for non-EU migrants arrested trying to get into Greece and Bulgaria, and how an EU organisation seems to care more about ‘security’ than basic human rights.

‘Nobody had time to stroke their noses’

One book begets another, at least that’s how it seems. You have intentions to read about Egypt, to start to educate yourself about a country you know little about but are soon going to visit. You have already bought several books, they are by your bed, but first you decide to read a book about Mongolia in the 1920s,

not because you have any pressing need to learn about this subject, but because it is a large hardback at the bottom of the pile of non-fiction you are definitely going to read (as opposed to the piles and shelves of stuff you might one day read). This book has been there so long (at least three years) that the sight of its spine induces a kind of shame, like that caused by those emails you receive from good friends, that you click on eagerly, that you enjoy, and then do not respond to for weeks, months, even though it would only take a few moments, five or six sentences, to adequately reply. And so you drag it out, dust it off, see how many pages it has, then dutifully start to read. You find yourself enjoying it. You did not know about the Czech Legion during WW1. You are amazed at the atrocities of Baron von Ungern-Sternberg. When you finish you look at the Egypt books, try to decide which to read first. You are not sure, and while you think, you look at the pile you will definitely read, then at the might-read pile, and there you find a book you only bought because it was £1, Peter Fleming’s, ‘The Fate of Admiral Kolchak’.

Again, you had had no thought to read about White Russian armies, but it does relate to what you have just read, and if you do not read it now, then when? And so you begin. You read about the armoured trains used on the Trans Siberian railway.

You read about rearguard actions against the Bolsheviks, and the stresses of command. This is Baron Wrangel’s description of General Slachtov, who was holding the Perekop Isthmus in the Crimea in 1920:

His face was deadly pale and his mouth never ceased to tremble, while tears streamed from his eyes… Incredible disorder reigned in his railway carriage. The table was covered with bottles and dishes of hors d’oeuvres; on the bunks were clothes, playing-cards and weapons, all lying about anyhow. Amidst all this confusion was Slachtov, clad in a fantastic white dolman, gold-laced and befurred. He was surrounded by all kinds of birds; he had a crane there, and also a raven, a swallow and a jay; they were hopping about on the table and the bunks, fluttering round and perching on their master’s head and shoulders

As for this account of the horses abandoned during the White Russians’ retreat from Omsk in 1919, you find it surreal and heartbreaking.

They were as tame as pet dogs, but nobody had time to stroke their noses. They stood in the streets ruminating over the remarkable change that had taken place in their circumstances. They walked into cafes. They wandered wearily through the deep snow. Droves of them blackened the distant hills.

After this, it makes complete sense to read a book about the Ukraine, then one about Armenia.

Tomorrow, you will write to Viktor, tell him you are well.

The Embrace

I have a story called ‘The Embrace’ in the Autumn 2011 issue of The Southern Review. Both this story, and its predecessor (‘The Ballad of Lucy Miller’, which appeared in the Spring 2009 issue) were chosen by editor Jeanne Leiby, who died earlier this year. I only met Jeanne through email, but I owe her a huge debt, not just for accepting the stories, but also for encouraging me to send more work after my first submission to the journal was rejected.

This is how the story begins, and as should be quickly apparent, it is another despatch from The World of Happy. The issue also features new poems by Sharon Olds, a wonderful poet you should check out if you’re not familiar with her work.

The Embrace

There is no excuse: buildings have windows, roofs and stairs; roads have lorries and cars. In her house there are knives, pills, and bleach. There is a gas oven. If after two years, Heather is not dead, it is because she’s a coward. All she does is say her prayers before she goes to bed. Dear no one, dear nothing, let something burst while I sleep. It does not need to be my heart, just an artery.

But every night her body fails her. Every day, she wakes.

She gets up and goes into the bathroom where there is a high window. Open it and fly beyond, say several bars of soap. Why is it these things that speak? Why not the shampoo?

She sits on the toilet, water leaves her. She flushes and puts down the lid. What was a toilet is now a step, which leads to another, as it does on a scaffold. She climbs up and opens the window; the sky is full of white clouds except for a gap that beckons. It will close, and never reopen, and so she must hurry. All she need do is lean out; gravity will help.

The problem is that the hole is over a cloud, which is above a roof, a window, a stretch of wall, a plaque that says ‘1898’. There is then another window, an intervening branch, and finally, the schoolyard, or part of it, a narrow stretch between portacabin and fence, and soon a bell will ring.

Heather climbs down, then turns on the shower. She takes off her underwear, waits— the water may still be cold —then gets into the bath. The water is warm, then properly hot, and it does not take long to wash. Soap on her face, soap under her arms, soap between her legs. Once this chore is done, she can close her eyes. Focus on water meeting her skin, the paths it takes down her back and arms; the glide of it down her legs. She does not think, hear words, see pictures. She is held by water.

The Yugosphere

My piece on the idea of a Yugosphere, and the problems of referring to the region that was Yugoslavia, is now up at Citizenship in South Eastern Europe (CITSEE), which is part of the Faculty of Law at the University of Edinburgh. There’s also lots of other good material on the region, including photo reportage and interviews.

Quoted

I was asked my opinion about recent violence in Xinjiang- here it is: CHINA: New Laws to Crack Down on Uyghurs – IPS ipsnews.net

Occupy, Prague

I have a post on the LRB Blog about the Occupy Protest in Prague last Saturday. Here’s some video of it as well.

The Book of Crows- A Review

My review of Sam Meekings’ The Book of Crows- a novel set in different time periods in China -is in the new issue of Edinburgh Review.

The Book of Crows by Sam Meekings (Polygon)

How did people think and speak a thousand years ago? The simple answer is: we don’t know. Without recorded speech, or transcripts, the best a historian can do is guess. So when we read a historical work of fiction what matters is not so much the accuracy of the characters’ thoughts and language, but whether they seem plausible. Sam Meeking’s second novel, The Book of Crows, attempts to ventriloquise characters from four different periods in Chinese history: a young girl in the 1st Century BCE who is kidnapped and taken to a brothel; a grieving poet in the 9th Century; a Franciscan monk in the 13th Century; and a low ranking civil servant in the early 1990s. What these disparate narrators have in common is that they encounter people determined to find a mythical book that contains the entire past, present and future history of the world.

Meekings is to be commended for his ambition in trying to weave these separate narratives together, not so much at the level of plot, but in terms of parallels between the different narrators. The poet, the kidnapped girl, and the civil servant all share a degree of fatalism, which accords with the ideas of predestination and fate raised when different characters debate whether the knowledge offered by the mythical book is more a curse than a blessing. ‘Rain at Night’, the story of the grieving poet, is by far the most affecting of the different strands. Though Bai Juyi‘s grief for his daughter is dealt with in a mostly oblique fashion, there is a delicacy and sadness to his narration. His discussion of poetry with the crown prince is an impressively nuanced scene that functions as both a literary and spiritual lesson. Though some of his expositions of Buddhist precepts feel a trifle forced (‘…for a while we shared our common experiences of finding solace in the words of the Buddha, in the first realisation of the illusory nature of the world and, therefore, of the self.’), for the most part the voice remains compelling, especially with each section’s epigrammatic closing statement (e.g. ‘I say a sutra that your shoes stay strong, that your palms stay open’).

Unfortunately, this lightness of touch is absent in the novel’s other strands. Though Meekings does well in conjuring the different places and time periods, in the main his characters fail to convince on either a psychological or linguistic level. ‘The Whorehouse of a Thousand Sighs’ is narrated in a faux-British manner that makes it very hard to believe that events are taking place in 1st Century BCE China. People speak of ‘winding us up’, being ‘pretty pissed off’, or say they ‘needed to pee’. When a cook says, ‘And knock me over if it doesn’t look longer than the bloody desert itself’, it verges on Cockney. There is also a general portentousness to these sections, not only in the dialogue (‘She didn’t just buy our bodies: she bought our lives, our hopes, our dreams, our futures’) but also in the sententious tone of the young narrator, who has a frequent (not to say unconvincing) tendency to deliver homilies such as ‘If you don’t speak of things, sometimes they get lost so deep that when you really need them the words are buried beyond your reach’ and, ‘Why can’t we keep our dreams to the present, to what we already have, instead of grasping at the future, the sky, the impossible?’

Another troubling feature about this strand is the almost romanticised treatment of a very young girl being abducted and forced to have sex with strangers. The girl rarely seems frightened, and when it comes to her first time, this is dealt with in a single, cursory paragraph.

The other two narrative strands are similarly plagued. The 13th Century monk’s expressions of prejudice and faith are so predictable that it is hard to retain interest. As for the civil servant in the 1990s (who also employs words like ‘wonky’ and ‘git’), some of his exclamations and statements are utterly implausible. ‘Thank the mighty Politburo!’ is a phrase that belongs only in propaganda. Meekings- who has lived in China –should also know better than to have his narrator say, ‘Some folks these days are nostalgic for the old Cultural Revolution’. This was certainly not the case in the early 1990s- it was far too fraught and recent a memory.

If The Book of Crows doesn’t succeed as either a collection of short pieces, or a novel (even one with a discontinuous narrative), this is partly because the attempt to recreate the thoughts and feelings of people from another time (not to mention another culture and language) must always carry a taint of the contemporary. In order for such characters and their worlds to be convincing, they need to be both linguistically and psychologically unfamiliar, so as to remove the reader from their language, time and culture. Otherwise the historical setting is what Lukacs called ‘mere costumery’. Though The Book of Crows offers us ‘curiosities and oddities’ from ancient China, its characters are too much of the present.

Reviews

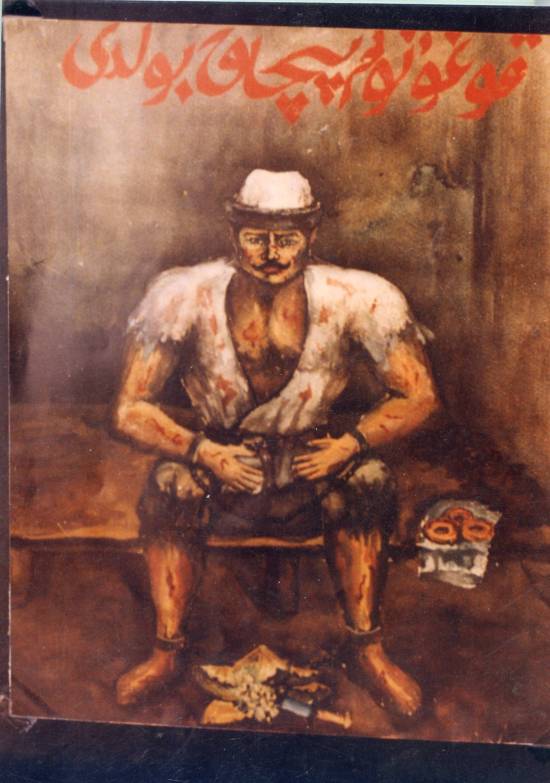

Sadur, who fought the Qing invaders, sitting in his cell, eating what appears to be a very reasonable lunch.

Here are the main reviews of The Tree That Bleeds so far- I’d like to express my gratitude to all the reviewers for their careful, thoughtful responses to the book (i.e. thank you for not giving it a mauling).

Thanks also to Scott Pack at Me And My Big Mouth for featuring it in his Quick Flicks section.

I don’t know if its gauche or amateurish to reply to some of the points they raise, but there are a few caveats- firstly, the SRB review was a pre-publication review, and some of its criticisms thus refer to an earlier version of the book (e.g. that it has no index, when the published version does- it’s first entry is ‘Awkward Sexual Moments’ (3 entries)). Secondly, that I corresponded with Josh Summers at Far West China, as he makes clear in his review. He quotes me accurately as saying that there were times when my anger gets away from me, but it might help to have the context in which I said that.

Josh asked me:

Your disdain for missionaries is readily apparent and I believe you did a wonderful job exploring the ignorant and uninformed hatred by both the Han and Uyghur. Were you hoping your reader would be able to make the connection between these two similar forms of bigotry or did you actually desire to paint such a picture of your expat co-workers?

My reply:

A tricky one. I hope I give a slightly more favourable portrait of Gabe than the others- but even now I still think there’s something unethical about a teacher using his position and access to push his ideas on students. I do think there are missionaries who do genuinely good work, but in the main I still have a problem with them being there (and not as teachers or health workers, but purely to proselytise). I think their actions endangered others. They certainly contributed to the atmosphere of paranoia and distrust (which I definitely succumbed to). Had it not been for them, it might have been easier to make more Han friends within the college.

But I can’t deny that there are moments in the book when my anger gets away from me. Believe it or not, I did tone some of this down, but in the end I left a lot of it, perhaps unwisely. I was trying to keep hindsight out of the book as much as possible, and this is one of the consequences. As is often the case with books like mine, the personal life of the narrator sometimes obscures the more interesting material. It occurs to me now that maybe some of this anger is due to the fact that of all the groups of people I tried to get to know, the missionaries were the most resistant- of all of them, only Gabe would talk about it. I don’t blame them for this, but it meant that I had little to go on in terms of understanding them and their motivatons. In some ways, I might have been better to just leave them out of the narrative. They aren’t really a significant part of what’s happening in Xinjiang, but they were a big part of my college world, and that’s why they loom fairly large.

Edinburgh Book Launch

Into the Abyss

A lot of wonderful looking films at the Toronto Film Festival, including Werner Herzog’s new documentary about death row inmates, which The Guardian bills as almost a comedy, a judgement supported by some of the clips. ‘Tell us about his hands.’

London Launch

The London launch for The Tree That Bleeds will take place at Arthur Probsthain, 41 Great Russell Street (just opposite the British Museum) between 6.30-8.

Mr Leonard Bernstein’s disclaimer regarding Mr Glenn Gould

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2OJB-9B1b0o

Mr Leonard Bernstein’s eloquent disclaimer regarding certain aspects of Mr Glenn Gould’s interpretation of the Brahms No. 1 Piano Concerto, before a concert in April 1962. He was particularly referring to Gould’s insistence that the entire first movement be played at half the indicated tempo. Gould was no lover of public recitals. He called them ‘the last remaining blood sport’. He gave his last public performance in 1964. He was 31. This perhaps give some indication of why he found it distasteful:

I believe that the justification of art is the internal combustion it ignites in the hearts of men and not its shallow, externalized, public manifestations. The purpose of art is not the release of a momentary ejection of adrenalin but is, rather, the gradual, lifelong construction of a state of wonder and serenity

Here are some pictures of Gould during recordings of Bach’s Goldberg Variations.

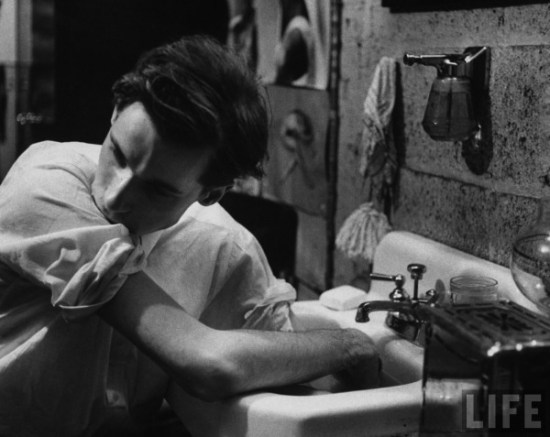

Gould soaking his hands before playing. He began with lukewam water then gradually raised the temperature.

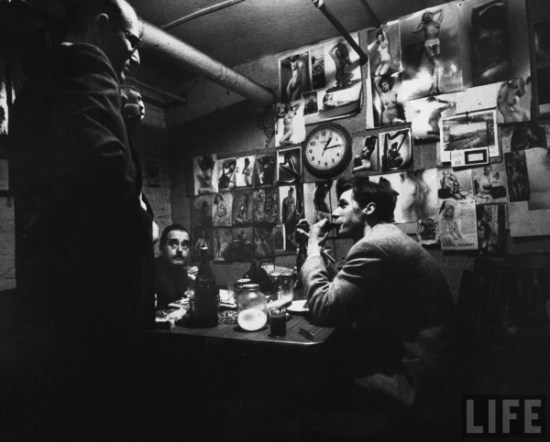

Gould laughing as engineers let him hear how his humming spoiled his recording of the Bach Goldberg Variations– after which he offered to wear a gas mask as a muffle. Gould would not let engineers remove the sound of his voice ‘humming’ in the backgound over fear that doing so would diminish the recording’s quality

Gould eating his lunch (graham crackers & milk cut with bottled spring water) while sitting at the sound engineers table

Oh, and if you’ve made it this far, here are the sounds themselves:

The end of the 1st movement of the Bach Concerto in D Minor

From the 1982 Recording of Bach’s Goldberg Variations, on which you can clearly hear Gould’s singing/humming:

Edinburgh International Book Festival Event

I’m delighted to have been asked to take part in an event at this year EIBF. I’ll be reading alongside Roger Hunt, whose book is about his experience as a hostage in Mumbai in 2008.

The event is on Friday 19th August, at 11.00 a.m. For more details of the event, click here

Ghulja, 1997.

This is a Channel 4 report I only found the other day. It contains pretty much the entirety of the video/photo evidence for the protests, at least the stuff you can find on the internet. This, after all, was before people had camera phones, well before YouTube. It contrasts sharply with how much footage there is of the Urumqi 2009 riots.

Arrests after the 2009 Urumqi riots

I have a new post on the LRB Blog about some footage of the arrests that followed the riots in Urümqi in 2009. The clip shows the fairly brutal treatment of suspects, not just by the police, but by the onlookers as well. It corroborates reports from eyewitnesses who spoke to Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch.

Extract from The Tree That Bleeds

Now up at The Chinabeat

Glasgow book launch

A television experiment

This first appeared on the TV version of This American Life. Cartoonist Chris Ware teams up with animator, John Kuramoto, to make a cartoon version of a true story about how a bunch of first-graders become warped by pretend-TV.

From a church in Baalbek

There’s a new Maronite church under construction in Baalbek, Lebanon. Inside there were naked mannequins and a stuffed fox. A crowned Virgin hovered in a cornflower sky on a painting in the chapel. This video is of a hymn that was being played through loudspeakers, calling people to prayer. I understood nothing of it, but found it moving nonetheless.

‘Civil Marriage, Not Civil War’

I have a new post on the London Review of Books Blog about the Secular movement in Lebanon. Here are some photos from the march on May 15th in Beirut.

The China Beat

I have a piece about the 2009 Urumqi riots on The China Beat, a great website that features a wide range of China-related posts.

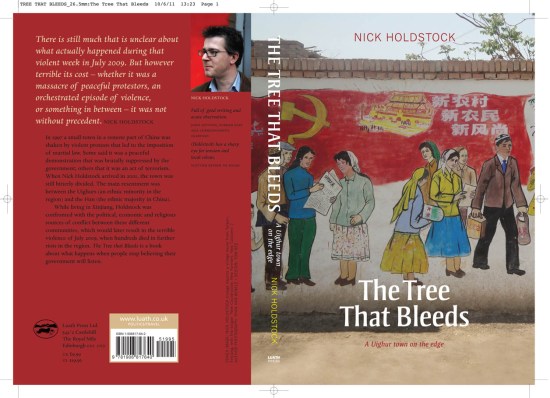

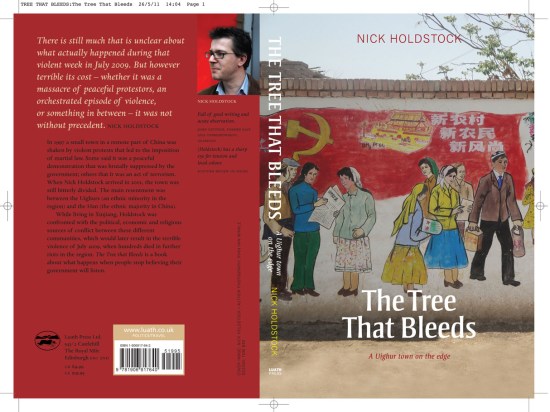

Cover

Beirut graffiti

I have a new post on the London Review of Books Blog about the sectarian graffiti in Beirut. As per usual, it features an act of stupidity on my part.

Poster Power

Some of the images I took in Xinjiang last year are in an exhibition in London at the University of Westminster (309 Regent St.). The exhibition runs until 14th July, for more info:

Poster Power: Images from Mao’s China, Then and Now

Found #9

Found in the same photo album as #8. Relation unknown. Reason for inclusion: the remarkable pallor of the girl in the most probably fake ‘YvesSaintLaurent’ sweater, which doesn’t seem as dramatic at low res, but is, I assure you, worth clicking on the photos in order to truly appreciate its deathly quality.

Found #8

3 pictures from a photo album with a paisley cover. The sea is probably the Mediterranean, the country Greece, judging by other less-interesting pictures in the album. There’s something very appealing about the woman’s evident happiness in the third picture, that makes her seem younger than in the other two, where she seems alternately calm and defiant. As ever, one struggles to understand how/why these pictures (and the album in which they were contained) ended up being thrown away, given that they seem to depict what was probably a good holiday. In the absence of any method of finding out, one can only wish her well.

Friday prayers in Xinjiang

Night Busking in Ghulja

Snake-oil

This gentleman was selling snake-oil in Yining market, and was doing excellent trade.

Apologies for the smallness of the video- I shot it sideways, then had to get an adult help me to rotate it (thanks Yaz!). Also thanks to A. for the following translation:

“No side effects on the human body, does not harm the skin, a universal cure for arthritis, high blood pressure, high blood cholesterol. It was prepared from boiling a mixture of various local (ethnic) herbal medicines. When you wash your body with it, it will cure and prevent back pain, leg pain, pruritus and other skin conditions resulted from the increasing cold in human body (cold here is like the 阴in the Chinese cosmic term 阴阳)”