A while ago I posted a list of US journals to submit to (courtesy of Bookfox), to which I’d like to add this list from Perpetual Folly, which ranks the journals according to how they are represented in the 2010 Pushcart Prize anthology. Though the two lists have considerable overlap (the domination of Ploughshares and Conjunctions for example) there are also some surprises, such as the Iowa Review and Glimmer Train being much lower down. I hope it will also be useful for alerting people to journals they may not be familiar with (my submissions to Noon and The Threepenny Review are already in the post…).

Inherent Vice, Chapter 17

PLOT- Coy tells Doc how he ended up being recruited as a snitch. Doc and Shasta reunite. Sort of. She makes him wonder if there’s any difference between he and Coy.

This is a thematically tight chapter, with its references to zombies, enslavement, addiction, being in the service of evil and irresistable powers.

p. 297

“You can’t always blame zombies for their condition,” says Doc, what may be only a joke, or instead a wider comment about our many forms of enslavement.

p. 297

Anybody understand why they call it ‘real’ estate’?” wondered Denis.

Good question.

p.298

Right now Coy had the look of sailor on liberty, willing to live inside the moment till he had to be back in some condition of servitude.

p.299

Further space reference, to Pink Floyd’s ‘Interstellar Overdrive’.

p.300

Coy’s method for kicking heroin is called, ironically, ‘Higher Discipline’. The irony is compounded by the fact that there is the incentive of ‘a once-a-year fix of Percodan, then regarded as the Rolls-Royce of opiates’. There is thus no recovery from addiction- just the substitution of one drug for another.

p.302

Coy makes the ‘karmic error of faking his own death’.

p.303

Nice mix of contradictory, yet truthful attributes in Doc’s self-description

He was back to his old wised-up self, short on optimism, ready to be played for a patsy again. Normal.

p. 305

Shasta tells Doc about the way Mickey treated her, how it was ‘so nice to be made feel invisible that way sometimes’. Here is a non-drug based method of dissociation- being treated so badly you cease to feel like a person. Even this, she suggests, can be a relief.

p. 312

has some karmic advice- ‘the best way to pay for any luck, however temporary, was just to be helpful when you could.’

p. 313

Shasta describes Coy and Doc as

cops who never wanted to be cops. Rather be surfing or smoking or fucking or anything but what you’re doing. You guys must’ve thought you’d be chasing criminals and instead here you’re both working for them.

Though it might seem that there is a difference between them, Doc is not sure. There is then, on p. 314, this passage.

Doc followed the prints of her bare feet already collapsing into rain and shadow, as if in a fool’s attempt to find his way back into a past that despite them both had gone on into the future it did.

At first this seemed hard to decipher- if the past had gone on into the future, that makes it seem like it hasn’t changed, so why need he try and find his way back to it? On third reading, I think it’s just a lament for a past (perhaps an imagined one) that led to a negative future. Which perhaps raises the question- how idyllic could such a past have been if it led to a present ruin? By imagining our past utopia, we must also undermine it, else there cannot be the Fall that leads to the present.

SCA talk

I’ll be giving a talk about Xinjiang to the Scotland China Association on Tuesday 9th March in Edinburgh. It will be in the library of The Friends Meeting House on Victoria Terrace (at the foot of the lane down from the Lawnmarket, at the top of the stairs down to Victoria Street). From 7-9 p.m.

Inherent Vice, Chapter 16

PLOT- Doc and Penny hook up again. The detective killed by Adrian Prussia turns out to be Bjornson’s old partner. Doc also finds a photo of Prussia in front of the Golden Fang. When he returns his office he finds Clancy Charlock and Tariq Khalil going at it on the floor. Tariq tells Doc about the arms deal Glen Charlock did with the WAMBAM. Later, Doc has a stoned conversation with Thomas Jefferson.

p. 278

When Doc needs to look at someone’s file, he says,

Ancient history, but it’s still under seal. Like till 2000?

There something disorientating about having a reference to the distant past with a projected event in the narrative future, which is actually our recent past. I’m not sure that we, as readers, can reconcile these different time periods, since one is imagined and the other is history, and maybe that’s the point. Whatever we take to be history, it isn’t a cohesive, continuous narrrative, but one of conflicting, contradictory accounts.

p.280

Further temporal distortion: when Doc and Penny are having sex, ‘for an untimably short moment Doc believed it was somehow never going to be over, though he managed not to get panicked about that.’

p.282

Further differentiation of the FBI and local cops, with the idea that the FBI are beyond the law. Then a long passage about ways of pereceiving and understanding from a supposedly addled state.

The clock up on the wall, which reminded Doc of elementary school back in San Joaquin, read some hour that it could not possibly be.

What matters here, I think, is disbelief- it is not that the situation (1970s America, or that of the present) was impossible, or even implausible, more that ‘we’ told ourselves it was. Such denial of the we-did-not-think-it -could-ever-possibly-get-this-bad variety is of course a contributory factor.

The passage continues:

Doc waited for the hands to move, but they didn’t, from which he deduced that the clock was broken and maybe had been for years.

Another interpretation would be that that time (as a index of change) has stopped. If the hands are not moving, it is thus not because the clock is broken, just that there is nothing for it to measure. This ties in with the whole idea (which I don’t have much use for) that there is a ‘crisis of historicity’.

Yet another interpretation is that it is ‘the time’ (i.e. society) which is broken. However, there is still the possibility of learning something from what seems to be broken (as there is from a paranoid supposing).

Which was groovy however because long ago Sortliege had taught him the esoteric skill of telling time from a broken clock. The first thing you had to do was light a joint… After inhaling potsmoke for a while, he glanced up at the clock, and sure enough, it showed a different time now, though this could also be from Doc having forgotten where the hands were to begin with.

Thus the means by which this knowledge is gained contaminate the answer.

p.283 Further reference to ‘ancient history’ (at least the third- the other being a reference to The Flinstones’ theme song).

p.286 In the photo of Adrian Prussia, the Golden Fang is described as ‘riding calmly at anchor in some nameless harbour, slightly out of focus as if through the veils of the next world’. This latter reference may refer to the future, and also our present.

Sauncho freaks out when he watches The Wizard of Oz on a colour TV, what is partly a stoner over-reaction, but also a commentary on the distorting effect of TV.

-the world we see Dorothy living in at the beginning of the picture is black, actually brown, and white, only she thinks she’s seeingit all in colour- the same normal everyday color we see our lives in. Then the cyclone picks her up, dumps her in Munchkin Land, and she walks out the door, and suddenly we see the brown and white shift into Technicolor. But if that’s what we see, what’s happening with Dorothy? What’s her ‘normal’ Kansas colour changing into? Huh? What very weird hypercolor?

p.288

In the previous chapter I wrote that Pynchon is rarely cynical about love. However, when Petunia says ‘Oh, Doc. Love is the only thing that will ever save us’, his only response is ‘Who?’ It is not love that is the problem- more the notion of ‘us’- and the questions of who can we trust, and what constitutes a bond.

p.293

The commodification of resistance and murder.

I been seein these T-shirts and shit? Like Manson’s mug shots with Afros airbrushed onto them, that’s real popular.

There is thus the suggestion that these are equivalent, in their status as icons, and that this matters more than what they stand for. This is certainly true of the variations of Che Guerava seen on T-shirts.

p.293 also has a too long to type out passage of paranoia (or dead on commentary) which, after a long list of paranoid supposings, asks

And would this be multiple choice?

It is thus not necessarily a question of only one of these terrible supposings being true. That could even be the best we can hope for.

p.294

Thomas Jefferson (also appears in Mason & Dixon, p.385) speaks to Doc:

So! The Golden Fang not only traffick in Enslavement, they peddle the implements of Liberation as well.

Though this is a reference to guns, it can also be a reference to drugs- the depressing thing being that both of those, whatever their revolutionary potential, are just further commodties.

Beheaded by a laser beam

I haven’t been able to watch TV news in years, mostly due to the sterling efforts of Mr Chris Morris on programs such as The Day Today and Brass Eye.

But we all need booster shots, and here is one courtesy of Mr Charlie Brooker.

‘Non-buyers of carrots and turnips’

From left: Erik Ross, Lillian Ross, Matthew Salinger, J. D. Salinger, and Peggy Salinger, in Central Park.

The first rash of obituaries for J.D. Salinger seemed to add little to what we had known for years. That he had removed himself from the world (at least, the literary one) for decades, only emerging to defend his privacy, albeit sometimes at the cost of it. That he had been writing… something during this time, but what this was, and whether we might dare to hope to see it, was no more certain than it had been for the last four decades.

However, now that the news cycle has moved on slightly (and perhaps also now that it is clear that this is not a hoax), people who had known Salinger are starting to come forward. Some of these are fairly minor, as one might expect from people who only had glancing, professional contact with Salinger (such as Tim Bates, who corresponded with Salinger whilst working at Penguin, in the far distant days before he was my agent for a brief time. About this, let it merely be said that, like Salinger, I too remember him in my nightly prayers) whilst others are from people with a deeper connection, such as Lilian Ross of the New Yorker, who talks of his love for Emerson’s dictum that

“A man must have aunts and cousins, must buy carrots and turnips, must have barn and woodshed, must go to market and to the blacksmith’s shop, must saunter and sleep and be inferior and silly.” Writers, he thought, had trouble abiding by that, and he referred to Flaubert and Kafka as “two other born non-buyers of carrots and turnips.”

Ross’ piece is the first one to make me recall what I prize most in Salinger- not the talk of phonies and fakes, but the unswerving belief in innocence. What I would like to be able to call Goodness. There are whole clusters of feelings we spend most of our adult lives avoiding, because of the risks they involve, because we lack the opportunity, or courage- these are what Salinger gives voice to. These are why it is worth reading (and re-reading) Franny & Zooey, Seymour: an introduction, and For Esme with Love and Squalor.

Lynch’s Interview Project now free

There are now 80 (and counting) of these short interviews with ordinary people all over the US. Though I have only seen a few so far, each has the ring of the genuine. Each will only take 3-4 minutes of your time. I reccommend no. 67 (James Flory) as a place to start.

‘The boy’ in New Leaf 26

Wyatt Mason on Celine

Wyatt Mason, whose Sentences blog for Harpers is much missed, writes in the NYRB about Céline, not least his anti-semitism, one of the more virulent strands of his misanthropy.

To read any single novel by Céline is to receive, in a bracing style, a hysterical primer on the abjection of being. To read them all is to register a unique species of racism: a hatred not of particular elements of humanity but of the human race as a whole. Thus Jean Giono said of Céline’s writing, “If Céline had truly believed what he wrote, he would have killed himself.”

Inherent Vice, Chapter 15

PLOT- Doc returns to LA, only to find that Shasta has returned. They meet, and she assures him she’s fine, but nothing really is said. Doc has several meetings with an increasingly emotional/unsettled Bigfoot, who reveals that the LAPD is itself prone to intrigue and paranoia. He warns Doc not to investigate the death of ‘El Drano’ (aka Leonard J. Loosemeat), Coy Harlingen’s heroin dealer (and thus a suspect in Coy’s ‘death’). When Doc talks to Leonard’s partner Pepe, he learns that Adrian Prussia, a major loanshark, may have paid Leonard to off Coy. Bigfoot adds a further twsit by telling Doc that he thinks Prussia is involved with the murder of a detective in the LAPD, which Internal Affairs are trying to hush up. Doc decides he needs to look up Penny…

p. 256

‘Around nightfall Tito let Doc off on Dunecrest, and it was like landing on some other planet.’

This sense of dislocation (**which happens a lot to the reader of Pynchon- he refuses to let you get settled in any time period) mounts, leading Doc to wonder if

Tito had actually dropepd him in some other beach town… and that the bars, eateries and so forth he’d been walking into were ones that happened to be similarly located in this other town

How should we read this? As a fear of homogenity? That the structures of command and control are the same everywhere? That there is a spatial equivalency between different places, in the same way that different historical moments are presented as equivalent (especially on TV).

p.257

When Doc runs into Denis, he doesn’t mind if it’s ‘somebody impersonating Denis’- even the appearence, or the fiction of his identity is preferable to nothing.

p.258

Even though ARPA (the proto-internet) is in its infancy, the FBI are already monitoring it.

p.261

Doc tries to watch the end of I Walked with a Zombie (1943) ‘but somehow despite his best efforts fell asleep in the middle, as so often before’.

There’s a fair few actions uncompleted in the novel- though most of these, as here, seem unimportant, perhaps Pynchon is arguing that it is symptomatic of a wider tendency. If TV shows, the internet and other forms of mass entertainement (the novel?) are what divert and distract us from an awareness (let alone an active resistance to) to the ills of the present, how badly must we be off if we cannot even attend to these properly? If we are distracted from our distractions?

p.262

As if some stereo needle had been lifted and set back down on some other sentimental oldie on the compilation LP of history.

This is a nice metaphor, which on closer inspection makes me wonder about describing history as a ‘compilation LP’. Something that is played over and over. Nothing but a collection of fragments. Things jumbled out of place. Things that may be skipped.

p.265

Leonard has a fine paranoid rant about loansharks.

They traffic with agencies of command and control, who will sooner or later betray all agreements they make because among the invisible powers there is no trust and no respect.

p.267

This deserves a closer look.

Lost, and not lost, and what Sauncho called lagan, deliberately lost and found again…

Unfortunately there is a mouse in my room which is really distracting me.

Um.

I had to go to the Pynchon wiki for this- it helpfully suggests that it can refer to the many disappearances and re-appearances in the novel, plus also Mickey’s conscience, and most of all, innocence and purity themselves (‘deliberately’ is here the key word).

p.272

Doc asks Bigfoot what seems almost a philosophical question.

“Can I say something out loud? Is anybody listening?”

Bigfoot’s reply encompasses fear, denial, and nihilism.

“Everybody. Nobody. Does it matter?”

p.273

A strong thematic statement about time, perception, and denial.

Yes and who says there can’t be time travel, or that places with real-world addresses can’t be haunted, not only by the dead but by the living as well? It helps to smoke a lot of weed and to do acid off and on, but sometimes even a literal-minded natchmeister like Bigfoot could manage it.

You have to get away from ‘reality’ in order to get closer to it. Man. Eerie connotations of the living being the ones doing the haunting.

The hot ticket this summer

Thousands are sure to flock to Lublin, in Poland, and not just for its associations with Jewish mysticism. This summer the International Pynchon conference is being held between 9-12 June. I’ll be giving a talk that may have some resemblance to the following abstract.

“Can you tell me, please, where is reality?”- Imagined Utopias in Inherent Vice

Pynchon’s novels contain multiple alternate time lines and realities, often in contradiction of one another. In this paper I argue that what interests Pynchon about such versions of history is not their ‘truth’ or otherwise (which is itself unverifiable) but how they are employed by people to meet different ends (ideological, social, personal), such as how to explain (and perhaps excuse) a present they view as lamentable, especially when they perceive themselves as being unable to effect meaningful change. One of the major themes of Inherent Vice is of a Fall from an imagined Utopia of the past- the sunken continent of Lemuria. Whilst this is a comment on nostalgia, and the need to believe that the past was better, it can also be seen as a way of avoiding responsibility for the ills of the present. By repeatedly invoking the idea of a ‘karmic adjustment’, Pynchon creates a pervasive sense of collective guilt, which whilst seeming to implicate ‘us’ (as a species, as a society) nonetheless spares us as individuals: the ‘sins’ for which we are paying were committed by others long before us. In some ways, this is the antithesis of the conspiracy theories beloved of Pynchon’s characters: there is no ‘they’ who can be blamed; there is only ‘us’. Whilst a long shadow hangs over the novel— cast by our knowledge, in hindsight, of the American political landscape from the 1970s to the present —Pynchon, as in his previous novels (most notably Gravity’s Rainbow) suggests that one ‘price’ for the ‘Fall’ has been our growing submission to technology. In the novel television, automobiles, and a proto-internet are all presented as being of equal (or greater) narcotic power to the illicit drugs consumed within the novel. These are shown to cause distortions of temporal and spatial perception that echo those which characterise the ‘crisis of historicity’ described by Harvey (1995), and more recently, Currie (2007) and Huehls (2009).

However, the novel is more than a straightforward paen for the ‘swinging sixties’. Just as the ‘sins’ of Lemuria are supposed by some of the novel’s characters to be the ‘cause’ of their problems, so Pynchon invites us, perhaps with a wink, to draw a link between the characters actions in his imagined version (or even, myth) of late 1960s California and our political present. One possible reading of the novel is that the many forms of escape, denial and avoidance exemplified by the characters (most of them drug-induced) have, by virtue of the political apathy they foster, contributed to the triumph of free-market values. But this seems a somewhat reactionary position for Pynchon to take. Given the distrust evidenced throughout much of his work for ideologies on both the right and the left, and also his habitual focus on the non-heroes of history (who are usually more observers than agents within the plot of the novels), Pynchon’s characters’ drug-induced retreats from ‘reality’— into fantasies of time-travel, alien abduction, or past-lives —can thus be considered the only form of resistance available, the nearest there is to ‘escape’ from the many traps of the present.

How do you catch a hold of yourself before it’s over?

Trailer for Win Riley’s forthcoming documentary about Walker Percy, appropriately featuring Richard Ford, who has spoken often, and eloquently, about the influence of Percy’s The Moviegoer on The Sportwriter.

Coming to a shelf near you…

I have a piece on the London Review of Books blog about the use of video trailers for literary fiction. It features a wonderful animation for Kazuo Ishiguro’s Nocturnes, and also one of Pynchon giving a monologue.

Inherent Vice, Chapter 14

PLOT- Tito drives Doc to the Kismet casino, a joint that has fallen on hard times. After placing a deliberately suspicious bet on the ‘Mickey book’, he is taken into the office of Fabian Fazzo, who tells him that Mickey was trying to build a new city out in the desert. In a private area he runs into the man himself, in the arms of the FBI. Out in the desert, he finds the half-completed, half-destroyed dream city of Arrepentimiento. Finally, Tito and Doc lose themselves in a Toob-fest.

Here, at around the two-thirds mark, a lot of the novel, both in terms of plot and also thematically, seems to come together.

In a Pynchon novel, this is somehow disquieting.

p.235 In the description of North Las Vegas- the neglected sibling of the Strip to the south -as being ‘away from the unremitting storm of light’ and this same glow then disappearing ‘as if into a separate “page right out of history”, as the Flintstones might say’, there is perhaps a somewhat optimistic message. On one level this can be viewed as prophetic- that all structures are subject to inevitable ruin. If this fate can befall North Las Vegas, there is no reason why the Strip, that accumulator of Profit (see Chapter 13) should not one day submit.

However, the presence of a second, also ruined city in the chapter, perhaps undermines this hope- unlike North Las Vegas, Arrepentiemento was envisaged by Mickey Wolfmann as as act of atonement, and it too was quickly destroyed. One reading of this is that in the world to come (which we live in) intentions count for even less against the profit motive.

p.238 One of Pynchon’s favourite tropes- the relationship between cartography and power.

He says when Americans move any distance, they stick to lines of latitude. So it was like fate for me, I was always supposed to head west.

And just for good measure there is both the invocation of manifest destiny and the colonisation of the West.

p.238 Doc and Fabian’s long conversation about what might have happened to Wolfmann, during which they run through all the possible alternatives, nicely trivialises the whole Quest aspect of the plot (and the genre). They’re only talking about these outcomes in terms of gambling odds, not because anyone particularly cares. From what little I know of classic detective fiction (Chandler, Hammett) this is very much a staple of the genre. One could, I suppose, construe a more depressing interepretation- that someone’s life is only worth discussing in terms of how it might yield profit.

p.240 Even money is not to be trusted.

The half-dollar coin, right? ‘sucker used to be ninety percent silver, in ’65 they reduced that to forty percent, and now this year no more silver at all. Copper, nickel, what’s next, aluminium foil, see what I’m saying? Looks like a half-dollar, but it’s really only pretending to be one.

p.241 Doc remembers his acid trip as ‘trying to find his way through a labyrinth that was slowly sinking into the ocean’. As well as being a description of the present (both then, and now) ecological and political crisis, it is also a reference to the sunken continent of Lemuria, suggesting, somewhat gloomily, that even our impending disasters are far from original.

p.243 When Doc glimpses Mickey Wolfmann, he has

the same look as he had in his portrait back at his house in the L.A. hills— that game try at appearing visionary —passing right to left, borne onward, stately, tranquilized, as if being ferried between worlds

It is, alas, only an attempt at appearing (as opposed to being) visionary. But perhaps it still counts for something- whether or not it does depends on how we view his building the city in the desert- whether it is a meaningful (albeit doomed) attempt at atonement.

We might also ask which worlds he is being ferried between.

p.244 The FBI agent accuses Doc and his ilk of being the ones to inspire Wolfmann’s guilt.

It’s you hippies. You’re making everybody crazy.

It is undeniably unpleasant to reflect on the inequalities of the world, and especially on one’s own complicity in this state of affairs. So many of the book’s characters are doing their best to retreat from the world, by any means- psychedelic, mystical, insanity.

Wolfmann’s mea culpa, which summarises a persistent sentiment of the novel:

I feel as if I’ve awakened from a dream of a crime for which I can never atone, an act I can never go back and choose not to commit. I can’t believe I spent my whole life making people pay for shelter, when it ought to’ve been free. It’s just so obvious.

It is, however, not in a dream that these things were done, but by himself, in reality. This kind of distancing suggests that even when admitting responsibility, he is still preserving a modicum of denial. Furthermore, whether or not the wrongness of his acts is ‘so obvious’ is perhaps not the point. People are able to supply a justification for even the most obviously heinous acts e.g. mass murder, bombing civilians, genocide, etc.

p.246 The wackiness of the Gilligan’s Island/Godzilla clash gives way to Henry Kissinger on TV saying “Vell den, ve should chust bombp dem, schouldn’t ve?” There is then a ‘lengthy honking’ which drowns him out.

On the one hand, the funny voice, and juxtaposition with Godzilla,, serves to satirise Kissinger. However, there is also an argument that TV, by presenting the banal and the serious in alternation, trivialises all it depicts. As for the lengthy honking, I’m starting to notice the way that Pynchon’s characters are often quick to change the subject when something of importance is said- the honking (from a car, not a goose) feels like more of the same.

p.247 Classic the-conspiracy-is-only-a-cover-for-the-real-conspiracy stuff

“Ain’t like this is the Mob. Not even the pretend Mob you people think is the Mob.”

p.248 Arripentimiento is ‘Spanish for ‘sorry about that’.’

Also on this page, Doc gives Trilium and Puck his rental car. This, and the amount of time devoted to Coy Harlingen and his wife, reminds me that Pynchon, for all his pessimism, rarely strays into direct cynicism- there is nothing ironic about the way love is portrayed.

p.249 ‘Like spacemen in a space ship, they were pressed violently into the seat’

Further images of moving into the future- which, I think, is maybe what we, as readers of this historical novel, end up doing to the characters, in that we relate them to our present.

Is the idea of ‘a wake-up joint’ a contradiction? Or a nod to the need to disengage with reality in order to be able to cope with it?

p.250 Out in the desert, ‘the zomes ahead, like backdrop art in old sci-fi movies, never seemed to come any closer’.

Nor, alas, does the promised future where harmony prevails.

p.251 Spatial distortion inside the zome.

More space, judging from the outside, than there could possibly be in here.

Some paranoia about how things, even when destroyed, cannot be ‘history’, “because they’ll destroy all the records, too”.

p.253 The disruption, then resumption of the TV signal occurs ‘as if through some form of mercy peculiar to zomes’.

Though TV has been portrayed in mostly negative terms in the book thus far, here, in the wreckage of a supposed dream city, the TV appears to be almost a necessary means of escape.

This TV theme continues on p.254, but here the tone seems to have shifted, and the TV, for Doc, is once again disturbing. Watching John Garfield’s last picture ‘before the anti-subversives did him in’ (again, the sense of the patterns, and repetitions, of history) was

Somehow like seeing John Garfield die for real, with the whole respectable middle class standing there in the street smugly watching him do it.

After a litany of TV scenes, there is this passage, which I will, if you’ll forgive me, allow to speak for itself.

And here was Doc, on the natch, caught in a low-level bummer he couldn’t find his way out of, about how the Psychedelic Sixties, this little parenthesis of light, might close after all, and all be lost, taken back into darkness… how a certain hand might reach terribly out of darkness and reclaim the time, easy as taking a joint from a doper and stubbing it out for good.

Doc didn’t fall asleep till close to dawn and didn’t really wake up till they were going over the Cajon Pass, and it felt like he’d just been dreaming about climbing a more-than-geographical ridgeline, up out of some worked-out and picked-over territory, and descending into new terrain along some great definitive slope it would be more trouble than he might be up to turn and climb back over again.

OK, what I will say about this is that it could be read as TV being one of the things to ‘reclaim the time’, literally as well as metaphorically.

A fair summary, I think

Scottish Arts Council Grant

I’m pleased to say I’ve been awarded a professional development grant by the Scottish Arts Council which will help fund a trip to China in March. The purpose of the trip is to visit my old students, most of whom are either in the south east, around Guangzhou (which can be considered the new workshop of the world), in the south, in Hunan province (far poorer, more agricultural) or in the far west, in Xinjiang. I’m primarily interested in how they’ve fared in the far more open (and far more perilous) labour market that developed in the last decade. While all trained to be teachers, many have found their way into other occupations (soldier, businessman, postal worker), often in regions far from their hometowns. It is also possible that I may visit some interesting places in Xinjiang and have interesting conversations, and that these conversations, should they occur, may or may not help me understand the events of last summer and autumn.

It looks like The Tree that Bleeds will be out in the summer.

Golden Hour Book 2 reviews

Some nice reviews for the GHB 2 (here and here), most recently in the Edinburgh Evening News by the wonderful Peggy Hughes. There’s also a thoughtful one in the latest Northwords Now (in the print edition, but soon to be online). The book can still be bought here.

Oh, and happy new year!

David Simon interview at Vice

A long, rich, rewarding interview with David Simon at Vice.

Inherent Vice, Chapter 13

PLOT- Bigfoot alerts Doc to a possible connection between Puck Beaverton (one of Wolfmann’s bodyguards) and Coy Harlingen. Blatnoyd’s death is revealed as being due to bites, as from a pair of fangs… Trillium Fortnight asks Doc for help finding Puck Beaverton… These names are really incredible… um… Doc and Trillium fly to Vegas, where they run into Tito, and after Trillium has sex with someone called Osgood, and two one-armed bandits spew out jackpots, Doc arranges to meet with Puck at the Kismet Lounge.

p.207

Time was when Doc used to actually worry about turning into Bigfoot Bjornsen, ending up just one more diligent cop, going only where the leads pointed him, opaque to the light which seemed to be finding everybody else walking around in this regional dream of enlightenment… never to be up early enough for what might one day turn out to be a false dawn.

Here we see again the fears of transformation, selling out, of missing out on the dream of enlightenment- although you know it is most likely a delusion, it is still one you crave, and perhaps, need.

p.209 Even Bigfoot falls prey to the paranoia (or the very real sense of worse times to come) in his talk of

“the evil subgod who rules over Southern California… who off and on will wake from his slumber and allow the dark forces that are always lying there just out of the sunlight to come forth?”

and how much closer they are ‘to the end of the world’.

p.214

“Everybody’s time is precious,” philosophized Bigfoot, reaching for his wallet, “in its own way.”

This feels like a comment on how people are inevitably present-centred- how easy it is to feel that the time in which one lives is distinctive and special. But if each time is precious, then perhaps none of them is.

p.231

A nice description of a slot machine that seems to recapitulate political history:

A long line of half-dollars went disappearing down a chute of yellowing plastic, the milling around the edges of the coins acting like gear teeth, causing each of the dozens of shining John F. Kennedy heads to rotate slowly as they jittered away down the shallow incline, to be gobbled one after another into the indifferent maw of Las Vegas.

Thus politics is only something that drives and feeds the profit motive. Las Vegas, as a Marxist economist comments on p.232, is arguably the purest form of capitalism for it

produces no tangible goods, money flows in, money flows out, nothing is produced. This place should not, according to theory, even exist, let alone prosper as it does. I feel my whole life has been based on illusory premises. I have lost reality. Can you tell me, please, where is reality?

Perhaps this corresponds to the bewilderment that greets the end of history (in a Marxist sense).

Pynchon’s quest to ‘keep scholars busy for several generations’

Green cords, purple shirts, teenage groupies, weed and cheeseburgers: favourites of Pynchon in late 1960s California, which also crop up aplenty in Inherent Vice. More in Bill Pearlman’s account of those days in the LRB.

Inherent Vice, Chapter 12

PLOT

Doc pays a visit to the Chryskylodon ‘laughing academy’, where he runs into (again) Coy Harlingen, who expresses doubts that he can ever ‘get out’ of his involvement with various powers. Wolfman’s missing tie, with the nude of Shasta, is seen on an orderly. Denis’ flat gets trashed, and not even by him. Doc pays a home visit to one of the volunteer police force who were involved in the battle in chapter… 2?3? And then there is a dream in which Doc is a child and does not understand death.

p.188 Ominous talk at Chrskylodon of their ‘Noncompliant Cases Unit’, ‘not quite operational but soon to be the Institute’s pride and joy.’

Also, a spatial distortion where Doc has a feeling that Sloane is close by, but ‘in some weird indeterminate space whose residents weren’t sure where they were, inside or out the frame.’

p.190 Further pessimism about the direction of things:

The world had just been disassembled, anybody here could be working any hustle you could think of, and it was long past time to be, as Shaggy would say, like gettin out of here, Scoob.

p. 194 ‘Back in junior college, professors had pointed out to Doc the ussful notion that the word is not the thing, the map is not the territory.’

The whole signs and signification thing. Not sure whether this is meant as giant reminder of the unreality of the text.

p.195 Small joke about use of the ARPA (the proto-internet) being like ‘surfin the wave of the future’. Then it is said to be ‘like acid, a whole ‘nother strange world- time, space and all that shit’. Down the rabbit hole of this sentence there is a big (though possibly trivial) debate about what globalisation and the internet have allegedly done to our sense of time (and in particular, sense of history) and space. Believe me, I know. I just wrote 3,000 words on it. Postmodernism and Time and Narrative and…

p.205 A short, but disquieting dream sequence, in which Doc is with a kid who resembles his brother, but is not, and a woman who resembles his mother, but is not. They are in a diner and the young Doc asks when a waitress named Shannon is coming back.

“Didn’t you hear what the girl said? Shannon’s dead.”

“That’s only in stories. The real Shannon will come back.”

“Hell she will.”

“She will, Mom.”

“You really believe that stuff.”

“Well what do you think happens to you when you die?”

“You’re dead.”

Why would he, or anyone else, think that people only die in stories?

I’m not sure if the following (on p.206) helps, or just makes it both sadder and more mysterious.

And now grown-up Doc feels his life surrounded by dead people who do and don’t come back, or who never went, and meantime everybody else understands which is which, but there is something so clear and simple that Doc is failing to see, will alwyas manage not to grasp.

It’s almost a lapse in the main genre register of the book, which so far hasn’t really been interested in a richer set of emotions for Doc (though it would be less distinctive in Against the Day or Mason & Dixon). If I had already finished the book (as would have been sensible, rather than this chapter by chapter, twice, approach) I would know whether it marked a shift in emotional tenor, as Doc realises that the 60s (whatever they were) are definitely over.

DFW story in The New Yorker

I can’t recall the last time I saw a story in the New Yorker by a writer I hadn’t heard of (i.e. someone like me). From what I gather, a lot of the ‘biggest’ (by which I mean prestige, not size) writers have exclusive contracts with them, so there is really no reason for them to ever look in the virtual slush pile- I’m amazed they even accept unsolicited fiction.

This, however, is not to complain. All the fiction they publish is available free online, which is why I am able to urge you to click your way to the late David Foster Wallace’s beautiful, sad, and very genuine story ‘All That’ which I’m guessing is an extract from his unfinished novel, The Pale King, due in April 2011.

Entitled

I’m currently reading (and much enjoying) Frank Kermode’s (1967) The Sense of an Ending, which is about how narratives, both spiritual and profane, use their respective ends (often death, and the Apocalypse) to structure themselves.

The age of perpetual transition in technological and artistic matters is understandably an age of perpetual crisis in morals and politics. And so, changed by our special pressures, subdued by our scepticism, the paradigms of apocalypse continue to lie under our ways of making sense of the world.

There’s a piece on him in today’s Guardian, and he’s also giving a talk on ‘Shakespeare and the Shudder’ on February 8th at the British Museum. He has two new books coming out, one on E.M. Forster, the other a collection of pieces from the LRB.

Crumb and Speigelman talk comics

A very enjoyable account of their conversation from The Rumpus:

Spiegelman has drawn Santa pissing in the snow next to a “Remember the Homeless” sign, Bill Clinton getting a blowjob in front of a firing squad. In regard to a published New Yorker cover depicting a Hassid kissing an African-American woman, Spiegelman says a girl wrote him a letter saying how nice it was for him to have drawn Abraham Lincoln kissing a slave.

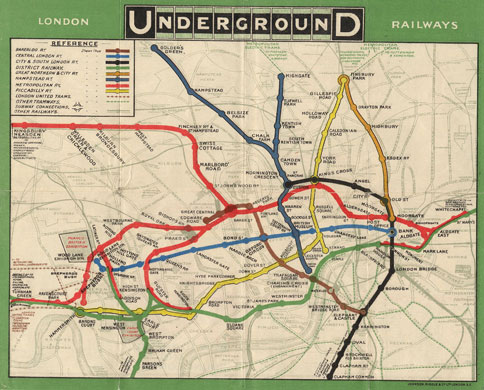

Underground

The Guardian has a nice visual history of the London Underground map, including several pre-diagrammatic versions like the one pictured above.

Found #7

A Working Life

A friend of mine, Erlend Clouston, has been writing a series of wonderful pieces for The Guardian about some of the less glamorous and yet most essential jobs in Scotland. I particularly reccommend the piece on the The Forth bridge painters and the one about a marine engineer on the Calmac ferries.

For some reason, these have appeared in the Money section of the Guardian, rather than in G2, perhaps because they have insufficient celebrity or scandal content. By putting them in a section which few of us read, the Guardian seems to be affirming the notion that these jobs, though essential, are better off unseen.

The Birds of Midway Atoll

I wish the bird in this photo were part of some shamanic ritual, or failing that, an art piece by a hermit who lives on the coast of Novia Scotia. Unfortunately, this is not the case. It, and the other photos below, were taken by Chris Jordan a month ago on Midway Atoll.

These photographs of albatross chicks were made just a few weeks ago on Midway Atoll, a tiny stretch of sand and coral near the middle of the North Pacific. The nesting babies are fed bellies-full of plastic by their parents, who soar out over the vast polluted ocean collecting what looks to them like food to bring back to their young. On this diet of human trash, every year tens of thousands of albatross chicks die on Midway from starvation, toxicity, and choking.

To document this phenomenon as faithfully as possible, not a single piece of plastic in any of these photographs was moved, placed, manipulated, arranged, or altered in any way. These images depict the actual stomach contents of baby birds in one of the world’s most remote marine sanctuaries, more than 2000 miles from the nearest continent.

There’s something about these pictures, and also Lu Guang’s, which troubles me, and not just because they starkly demonstrate the degree to which we have devastated our environment. What I find equally upsetting is how beautiful they are- as if even pollution now has its own aesthetic. Even as we push species into extinction, and ecosystems into radical change, we are making art from these actions. The fault, of course, is not in the photographers, but in those who provide subjects for them.

Cormac McCarthy Interview

A rare, intriguing, and somewhat provocative interview with Cormac Mccarthy and ‘The Road’ director John Hillcoat at the Wall Street Journal.

I don’t find it surprising that he describes the ‘800-page books that were written a hundred years ago’ as ‘indulgent’, though I cannot agree. McCarthy has said he has no interest in authors who do not ‘deal with issues of life and death’, but it seems to me that there are other, equally valid concerns for an author, some of which cannot be dealt with in a concise manner.

Inherent Vice, Chapter 11

PLOT

Doc gets a postcard from Shasta that reminds him of when a Ouija board sent them on a fool’s errand. When he revists the location he finds a golden building shaped like a fang. Inside he meets Japonica Fenway, a girl from a previous case, who has wraparound hallucinations. After Denis crashes his car, Doc takes it to Tito Stavrou, who tells him he was supposed to pick up Wolfman from Chryskyolodon, but he never showed. And that Chryskylodon is, at a push, Greek for ‘Golden Fang’.

p.163- An amusing alternative postal delivery system- ‘catapult mail delivery involving catapult shells, maybe as a way of dealing with an unapproachable reef’.

p.165- A little extra sensory paranoia to add to all the fears about the living

Around us are always mischevious spirit forces, just past the threshold of human perception, occupying both worlds, and that these critters enjoy nothing better than to mess with all of us still attached to the thick and sorrowful catalogs of human desire.

p.166- During a torrential storm Doc imagines floods that lead to the ‘karmic waterscape connecting together, as the rain went on falling and the land vanished, into a sizable inland sea that would presently become an extension of the Pacific’. Lest we miss the reference to Lemuria, Sortilege has a dream about it, where she reveals that ‘We can’t find a way to return to Lemuria, so it’s returning to us’ (p.167). Just because this is an imagined Eden, it is no less potent (and perhaps painful). Once again, we are dealing with the Fall. Which is perhaps the only tolerable way to explain the present. At least there is the comfort that in the past things were different.

p.166- Doc and Shasta, whose relationship is all but over, make out in a car (this is a flashback) just so they can forget ‘for a few minutes how it was all going to develop anyway’. This is pretty much a synedoche of the novel.

p.170- The Golden Fang Procedures Handbook has a chapter on ‘Hippies’.

Dealing with the Hippie is generally straightforward. His childlike nature will usually respond positively to drugs, sex, and/or rock and roll’

p.171 Doc has a vision of ‘an American Indian in full Indian gear, perhaps one of those warriors who wipe out Henry Fonda’s regiment in Fort Apache (1948)’. Though a comic moment, this is also a nod to a history of disposession, of massacre and counter-massacre.

p.172 Japonica’s delusion (‘actually visiting other worlds’ p. 175) is not without its truth, and also recalls the figures from the future in Against the Day.

Among those who could afford to, a stenuous mass denial of the passage of time was under way. All across a city long devoted to illusory product, clairvoyant Japonica had seen them, these travellers invisible to others, poised, gazing, from smogswept mesa-tops above the boulevards, acknowledging one another across miles and years, summit to summit, in the dusk, under an obscurely enforced silence.

p.176 Another ominous technological development, when Doc sees people listening to music on headphones,

in solitude, confinement and mutual silence, and some of them later at the register would actually be spending money to hear rock ‘n’ roll. It seemed to Doc like some strange kind of dues or payback. More and more lately he’d been brooding about this great collective dream that everybody was being encouraged to stay tripping around in. Only now and then would you get an unplanned glimpse at the other side.

The disturbing implication here is that all of the experimentation and freedom of the 60s actually helped the interests of capital and authority. That the last thing the latter wanted was a public fully engaged with actuality.